For the last several years, the biggest question in retailing has been the competition between old-school bricks and mortar stores and the rise of ECommerce and online retailing. Here I extend the work done for my recently published report on retail trends to take a closer look at the future of the industry.

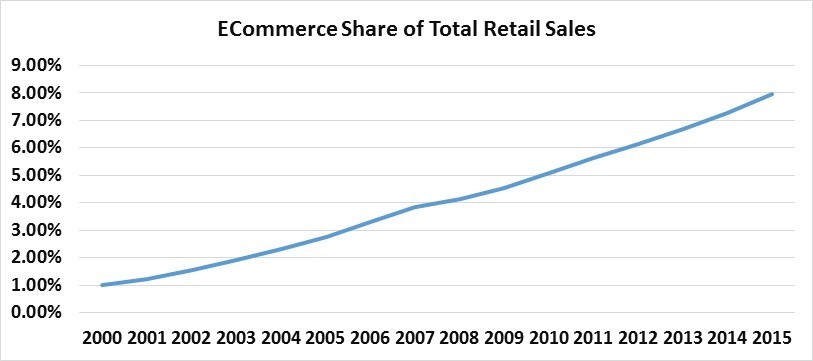

The first and most surprising thing to most people is that ECommerce represents less than 10% of total US retail sales. While it is very high in some categories, including books and music, it is tiny in some of the biggest categories such as food, drugs, and automobiles. In the following pages, I exclude gasoline stations because the price of gasoline is so volatile as to skew the past basis for future projections. This has been especially true the last ten years. Gasoline is, however, a major category (over $400 billion in annual retail sales) which is not likely to be sold online.

Any look at the future must start with a view of the past. As Steve Jobs said, “You can’t connect the dots looking forward. You can only connect them looking backward.”

The Past

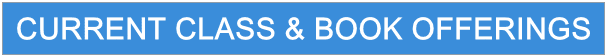

Over the last 15 years, total US retail sales excluding gasoline stations have generally grown 3-6% per year, as shown below. The industry took a huge hit in the great recession of 2008-2009, showing declines, came back the next two years, then growth weakened a bit in 2012 and 2013. Since then, growth has been accelerating modestly.

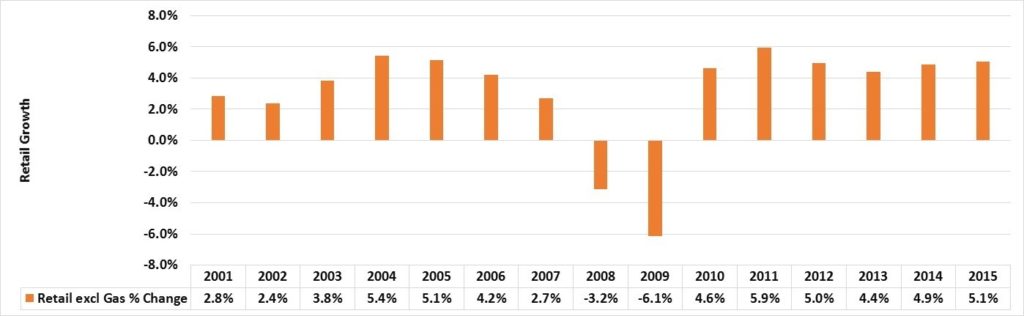

Over these same years, total ECommerce sales growth has shown a similar pattern, although at a much higher rate of growth. While the recession did not cause a drop in sales as it did in overall retailing, it made a big dent in the growth, temporarily. The pattern since the recession has been parallel to overall retail trends, accelerating in 2010 and 2011, slowing in 2012 and 2013, then accelerating again through 2015.

Amazon

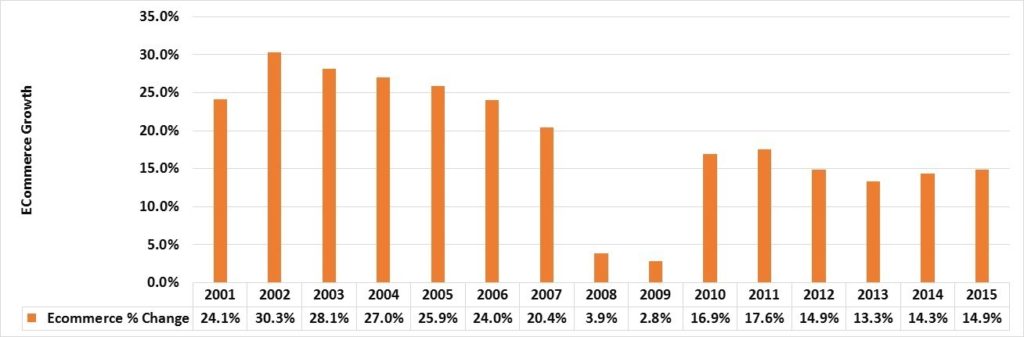

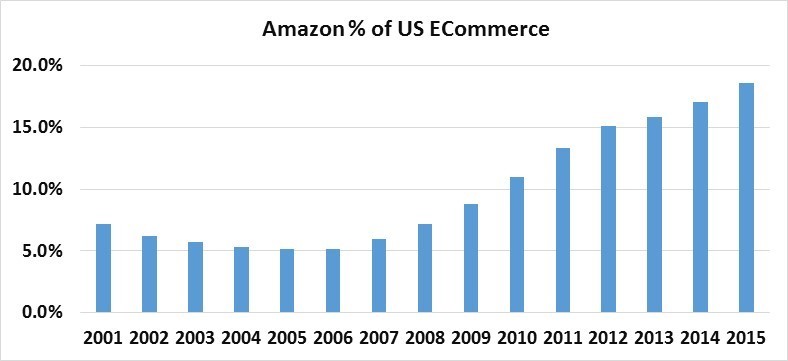

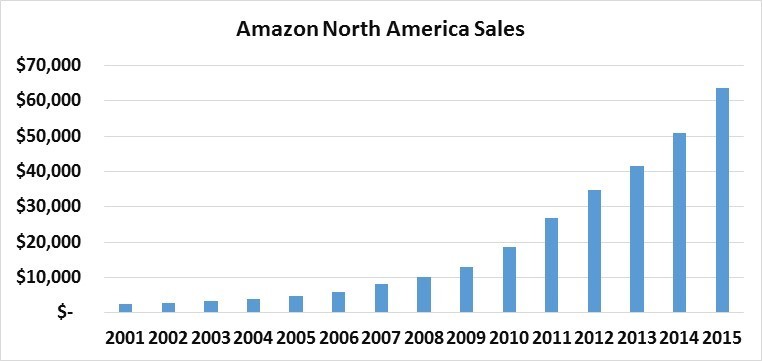

As the biggest force in ECommerce, representing about 18% of US ECommerce in 2015, Amazon is worth looking at individually. Amazon has been on its own track, performing a bit differently than either total retailing or total ECommerce. It was accelerating strongly before the recession, then hit less hard by the recession, but then came back stronger than ever. Amazon’s growth rate has not achieved historic peak rates over the last three years, but like total retailing and total ECommerce, it accelerated over this period.

Two things have been consistent about Amazon: a remarkably increasing share of US ECommerce since 2006 and growing sales:

(Amazon sales are North American total, so these values are slightly overstated.)

(Dollars in millions.)

The Future

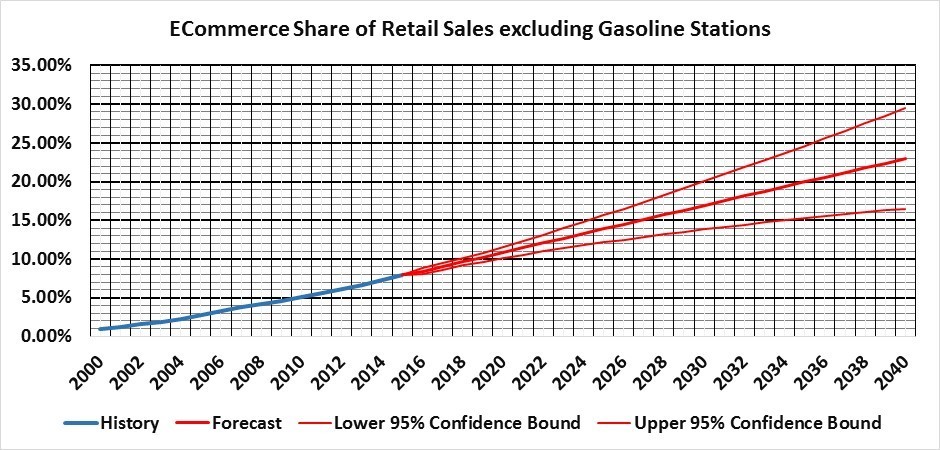

What does this portend for the future? Using data from the Census Bureau’s Economic Census (taken every 5 years) and more frequently collected data, we see that the ECommerce share of US retailing (excluding gas stations) follows a consistent pattern of growth.

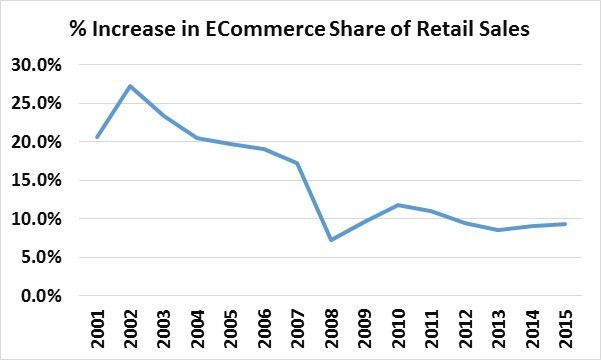

However, as one might expect in a maturing time series, the growth rate is slowing. The chart below shows the percentage increase in ECommerce’s share of total retail sales. (For example, an increase from 4% of retailing to 5% of retailing would be a 25% increase in the share.) If we take out the sharp dip from the recession, it follows a relatively smooth pattern between 2002 and 2015, yielding some confidence that this trend will continue.

Using 16 years of historical data for a basis for projections yields the following curve going forward for the next 25 years. (The upper and lower bounds are the ranges within which the statisticians tell us there is 95% confidence that it will not be higher or lower than these levels.)

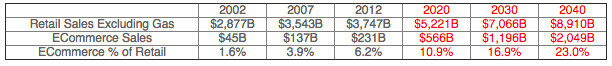

Using similar methods, we can also forecast total retail sales going out to 2040. This forecast assumes slowing retail sales growth, which is likely given the continuing shift from products to services in the US (and global) economy. We are more likely to be spending on healthcare, travel, education, entertainment, financial, and other services than just buying more “stuff.”

Combining the forecast of retail sales with that for the ECommerce share yields the numbers in the table below. (Note that actual results will reflect higher or lower than normal inflation, which we have not tried to predict here.)

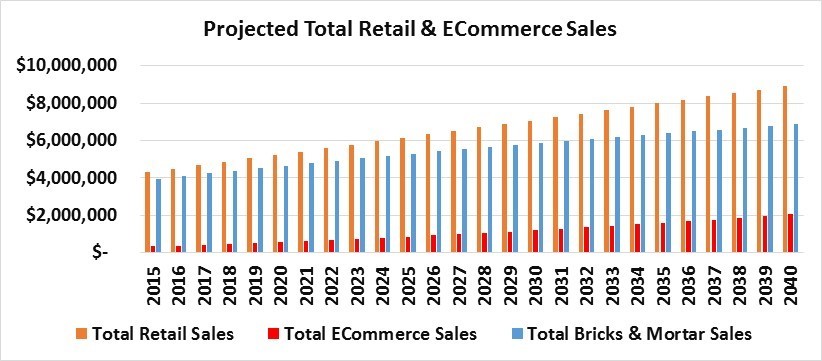

What does this imply for bricks and mortar stores?

(Dollars in millions, so that top line is $10 Trillion!)

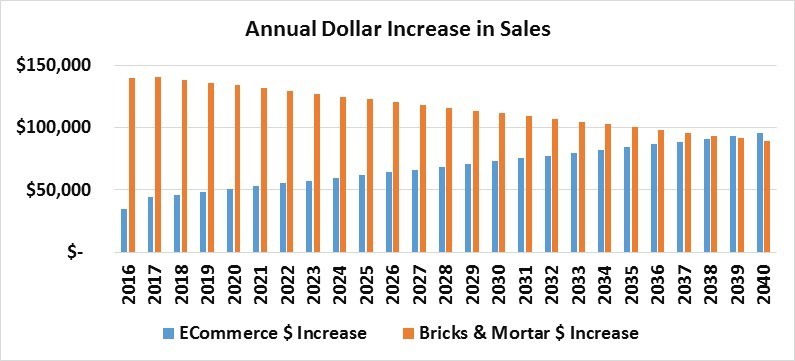

That is plenty of business to go around, but, if these projections prove out, within 25 years ECommerce will be getting over half of the growth in the retail pie:

(Dollars in millions, so the top line is $150 billion)

Implications

What does all this mean, both for ECommerce companies and for bricks and mortar retail operators? Some thoughts:

These changes are not happening overnight. The trends have evolved over the 20-year history of ECommerce, and will continue to evolve in coming decades. By 2040, Millennials will be in their 40s and 50s, and their children may not have the same tendencies. Like previous generations, they may rebel against the prior generation, possibly even using mobile devices less, or in different ways. History also teaches us that the leadership of top Internet companies can be very fragile. Remember AOL, Yahoo, Alta Vista, Egghead, and MySpace? Today’s leaders may not be tomorrow’s leaders. Amazon, because of their high “stickiness” (tracking past purchases, re-order buttons, one-click, Prime), may have more staying power than has historically been the case of Internet companies.

There are really two questions to be answered:

1. What will be the mix between sales via the Internet and via physical retail stores?

2. What will be the mix, even in ECommerce revenues, between companies dedicated to the Internet and those which descend from bricks and mortar retailers?

The above charts deal with the first question. It is safe to predict that more and more goods will be purchased using the Internet and mobile technologies.

But the second question is more complex.

I believe that in 10 years or so, we will not even be asking these questions in this manner. Virtually every successful bricks and mortar retailer will integrate the new technologies into their business. Already some old-line retailers like Macy’s are getting almost 20% of their sales via the Internet. And some ECommerce companies will open physical stores – Amazon has recently begun this process, though how far they will go remains to be seen.

This evolution is likely to parallel what we are beginning to see in the distribution of food. For decades, “food away from home” (restaurants) have been taking share from “food at home” (grocery stores). See my report for more on this. Today, more and more restaurants offer drive-through windows, parking spots for to-go pickup, and home delivery. At the same time, an increasing share of grocery store profitability (and customer appeal) comes from delis, cafes, and ready-to-eat meals. New “hybrid” concepts like Snap Kitchen are springing up. In thirty years, this trend is going to be even more pervasive. As will the hybridization of ECommerce and bricks and mortar, throughout retailing.

We can see this in the separation of the two concepts of “Multichannel” retailing (operating both online and physical stores) and “Omnichannel” retailing (fully integrating the shopping experience; seamless connections between stores and websites). Most of the great retailers have their live local inventory availabilities shown on their websites, and are beginning to integrate mobile apps into the store experience.

Still, the bricks and mortar retailers have a major challenge: how much physical space do they need and what should they do with it? Leases run long and are virtually impossible to get out of, outside of bankruptcy. Even if say Barnes & Noble decided tomorrow that they do not need their millions of square feet, it would take a long time to effect change. So what are they to do?

Here are six thoughts for retailers “stuck” with physical space:

First, be careful about closing too many stores without thinking it through. It is easy to underestimate the importance of having a visible physical presence – a big ad. Maybe that is what Amazon saw when they decided to open physical stores. Second, beware of the appeal of closing your weakest stores – many retailers have discovered the hard way that fewer stores also means less coverage of corporate overhead, and it’s easy to keep closing stores from the bottom up until none are left. Retailers should think geographically: regional and metropolitan store clusters are the most effective ways to leverage economies of distribution, oversight, marketing, and customer word-of-mouth.

Are there creative ways to improve the efficiency of your space utilization? One oversized Office Depot in Austin on a hot corner reconfigured to a smaller footprint, and leased the excess to a new CVS drugstore. For some of my own innovative concepts for the “experience economy,” I would love to get my hands on 50,000 square feet of selected Sears stores, virtually all of which are too big for the revenues they generate today.

Retailers need to return to the most fundamental “secrets” of the great retailers of the past. Macy’s big Herald Square store in New York City was doing $100 million a year in sales in 1929. It was a circus of activity. Hundreds of thousands attended the openings of big stores like Macy’s, and it was a part of everyone’s life and conversation. The great retailers provided guests with an exceptional experience. By the standards of 1900, even Apple’s great stores are not truly “electric.” People will go out of their way for interesting experiences. Not just the same old displays of the same old vendors, with most stores looking alike. (For much more on the classical principles of retailing, see my report.)

Retailers need to look at the total economy and see the rise of experiences and the shift to services. How can you participate in the rise of sports and recreation, of entertainment, of education, of travel, of health and financial services? PetSmart is to be congratulated on their complex moves into veterinary medicine, pet grooming, pet training, and pet boarding. All those categories likely have greater growth prospects than selling pet food and pet toys alone. TopGolf, IFly, and above all else the restaurant business attract new ideas and droves of customers daily. How can your store integrate these or similar ideas, even if on a smaller scale? In their glory days, the great urban department stores like Marshall Field’s ran massive restaurant operations that were among the best in town. Today, just as the restaurant industry has risen to prominence, most of them have abandoned these opportunities.

If one reviews the growth of different merchandise categories (see my report), drugs and health and beauty holds the greatest promise of future growth. Barnes & Noble has just begun an experiment with cosmetics in a few stores. Such paths will not be easy, but they take retailers into categories that are growing, that generate more frequent store visits, and that are more immune to the rise of the Internet (see projections for categories, below). Other areas which are less subject to ECommerce competition include the sale of automobiles, gasoline, home improvement products, and major appliances.

Perhaps above all else, retailers of old understood the highly social nature of commerce. Customers in the right store and right environment enjoy interacting with knowledgeable staff and even with other customers. The great department stores were leaders in their communities, with large auditoriums with continuous special events. They were engaged! If your store is no friendlier or truly “local” than Amazon, why should they bother taking the time to visit your store? (Your company does not have to be based in their city to become a key part of local life and conversation – study Starbucks.)

If layered on top of thoughtful progress toward Omnichannel, these ideas and others like them will insure the durability of the best retail companies. As has always been the case, new innovative competitors (like Amazon) take most of their business from the weakest and least successful retailers. Even with Amazon’s power in books, the best independent bookstores in America (such as Austin’s BookPeople) are today seeing sales and profit growth.

Projections for Key Categories

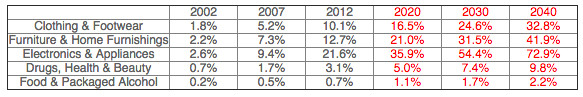

Using similar methods to those used above, based on actual data from the last three Economic Censuses, I show below histories and projections for the ECommerce penetration (market share) in five giant categories.

These values assume a continuation of the trends witnessed since 2002.

Clothing is now the largest single category of ECommerce sales, and the projections appear reasonable. The “Furniture” line is likely in large part smaller home furnishings; these numbers also seem reasonable.

Electronics and Appliances are more complex. The sale of audio and video equipment is somewhat cyclical, and dependent on new product introductions. Sometimes, like in computers (not included in the above table) and TVs, prices drop over time so it is hard to achieve top line revenue growth. There are limits on the potential of ECommerce in major appliances due to size, weight, and shipping issues, so I think the 72.9% penetration projection for 2040 is too high.

Drugs and food are where ECommerce has had the least impact, and these two categories generate huge annual revenue (see my report). My instinct is that ECommerce will make greater inroads in these areas than the 2040 projections of 9.8% and 2.2%, respectively. In order to achieve penetrations anywhere near those in clothing (or books or music), systemic changes will be required. For example, the way people buy food and the way the Internet sells food would need major changes. It seems unlikely that a purely ECommerce company, without partnering with major grocery store chains or wholesalers, could drive such dramatic change. At the same time, the market is so huge that even a small increase in these numbers – say from 2.2% of food in 2040 to 6.6% — would mean about an additional $62 billion in ECommerce sales in 2040.

I appreciate your interest and would love to get your input and questions on this newsletter here on LinkedIn.

Sign up for my newsletter if you would like future reports.

If you want more details on these numbers and my methodology, please email me at garyhoov@msn.com. I am also available for consulting on retail strategy, training, speeches, and other presentations.