|

Last week JC Penney of Dallas announced that in November of this year, they’ll get a new CEO. Ron Johnson, the man who created and developed the Apple stores, is coming to this well-established retailer. This is one of the biggest retail news stories in recent years. On my Hooversworld blog, I posted a video clip about my first reaction as soon as I heard the news (https://hooversworld.com/archives/3689?day=Tuesday).

Since then, there has been a lot more in print and online discussion about Penney and Apple. Penney’s stock shot up 17% by the time I converted the video to YouTube format and put it up on the web.

As a lifelong student of retailing and one who has followed Apple from its inception, I have plenty of thoughts about all this. Much of what I read online and in stock market analyses misses the mark; most writers don’t have much historical perspective. You really can’t understand what is likely to happen next unless you understand what has already happened. You have to understand the context of the game. I started to do another video to talk about all this, then realized it would never fit within YouTube’s 10 minute limit. So here it is in old-fashioned text form.

The American Department Store

First, let’s understand the overall retail situation and where department stores stand today. From about 1880 to 1960 traditional (or “conventional”) department stores ruled American non-food, general merchandise retailing. Probably peaking in the 1920s and 1930s, Marshall Field in Chicago, Wanamaker’s in Philly, Macy’s in New York, and thousands of others large and small led the way. They were the biggest advertisers, they generated the highest revenues per store, they employed the most people, they had giant downtown stores where the streetcars (and later buses) stopped right in front of their doors. Every city had at least two and some had a lot more. I have studied this business since I was 12, and spent 7 years working for two of the largest players. My first childhood dream was to someday run the local (Indianapolis) leader, LS Ayres & Co. The finest of several holding companies was Federated Department Stores, which operated under such local names as Lazarus, Rich’s, Burdine’s, Foley’s, Bullock’s, Bloomingdale’s, Filene’s, and Abraham and Straus.

(For a much more complete history of American retailing, watch my heavily illustrated video: http://blogs.mccombs.utexas.edu/mccombs-today/2010/04/ringing-registers-the-story-of-american-retailing/.)

Gradually, over the last 30-40 years, this segment of the industry went into decline. While some observers claim it was the rise of Wal-mart and the other discounters, or the decline of the middle class, I believe it was largely other factors which are not often mentioned, including:

1. These stores made much of their money selling women’s clothing. They ended up being run by people from that part of the business. These stores all had extensive toy, book, music, stationery, appliance, electronic, sporting goods, and other non-apparel departments, those carried lower profit margins. Over time they closed up those departments and became giant clothing stores, with some home furnishings. But in doing so they abandoned the growth departments. Demand for apparel, still a huge business, has grown much more slowly in the last 40 years than most of those other categories. Department stores, in fact, are no longer full line department stores. (Wal-mart and Target did not make this strategic error.)

2. These stores were individual companies with unique personalities. One store might have a great restaurant, the next was famous for its chocolates, some had antiques or products from around the world. Even long after they were consolidated into ownership groups like Federated, they were allowed to run on their own and maintain a local personality. If there were three different stores within a community – or within a mall – they had three different personalities and merchandise assortments. All this disappeared in recent years.

3. Part of that local spirit was a sense of community. If there was a disaster, aid was provided by the big local store. If there was a parade, they sponsored it. If there was a fashion show, it was in their auditorium. They made news. Again, even if owned by an out of town company, they were perceived and managed as local entities.

4. With specialized buyers for each category, these stores worked hard to find interesting, unique products – in all departments – that met the needs of their local market. Buyers were all powerful, and fascinating merchandise drove the business. These stores were exciting and they were differentiated from each other. Gradually, the stores turned more and more power over to national brands, and no matter what store you entered, you saw the same DKNY, Tommy Hilfiger, and Estee Lauder departments, the same look. At least in part, these stores abdicated their responsibility as creative merchants.

The upshot of all this is that, by the early 1990s, the most exciting stores in most American cities were no longer the local big department stores, they were either specialty stores like the Gap and the Limited, or Target.

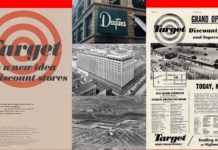

(Target is a separate and equally intriguing story, one of many discount store chains started by the old department stores in the 1960s in an effort to create an “upscale discounter.” This proved extremely hard for the old companies. Hard to lower your expense structure, hard to make discounting cool. Everybody gave up on this crazy notion. Everybody except Target, which emerged over time as the most exciting, best-merchandised general merchandise retailer in the land.)

No doubt the rise of discounters, the declining market share of enclosed malls (vs. park-at-the-door strip centers), the rise of superstores led by Toys R Us, and the rise of the warehouse/wholesale clubs contributed to the challenges of the department stores, but many of these trends were just as much a result of the above changes as they were causes of decline.

As is the case in many declining industries, the industry began to consolidate. No need for four stores in a mall, if all of them carried the same products and looked alike. The bulk of the industry ended up being part of Federated, which then selected its best known name, Macy’s, to apply to the vast majority of its stores. While I am pretty optimistic about Macy’s future, this part of retailing has lost tremendous market share since the 1960s and will never regain it.

The Rise of the General Merchandise Chains

Virtually all the commentators are calling JC Penney a “department store” and the company probably uses that term itself. But our thinking is clarified if we think of them differently.

The idea of a chain store, one with centralized buying, one where each store was a “cookie cutter” copy of all the others, one where there was little or no local differentiation, arose between 1860 and 1900 in the food business under the leadership of the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (“The A&P”). Only late in that century did someone try to apply this powerful idea to general merchandise, non-food retailing. His name was FW Woolworth.

And only in the 1920s did the two mail order giants, Montgomery Ward and Sears Roebuck, begin to open chains of lookalike retail stores carrying broad lines of merchandise. These were really the first department store chains. Their heart may have been in hard goods (tools, auto parts, sporting goods) but they carried every category under the sun. To differentiate them from the department stores described above (which had an entirely different “business model”), we called them “general merchandise chains.” By 1930, Sears was generating more revenue in its stores than it was in its catalog.

Starting early in the 20th century, James Cash Penney began opening small soft goods stores with a partner in each city. One of history’s greatest retailers, he was a firm believer in the Golden Rule, and named his first store after it. These stores carried socks and underwear, fabrics and inexpensive mass clothing. By the 1950s Penney had become a national chain, by the 1970s the second biggest general merchandise retailer after Sears. At the same time Penney stores became true department stores by adding auto parts, hardware, appliances, and other hard goods. Penney’s heart was never in these categories and by the 1990s they had dropped them and returned to their soft goods roots.

Snapshot in Time: 1973

In 1973 I graduated from the economics department of the University of Chicago and started my first job. I was the junior retail analyst (training under veteran analyst Charles “Pete” Wetzel) in Citibank’s Investment Management Group. For two years I was at the heart of the retail stock studying business.

Our three largest holdings reflected the three giants of the era – Sears the full department store national general merchandise chain, Penney the soft goods giant, and Kmart the upstart (first store 1962) discount industry leader. All were big, profitable, and historically great stocks to own.

The Big Three Hit the Skids

Here I will not go into the gory details, but by the 1990s, the three giants were all in the ditch. Sears began to fall asleep at the switch. Not unlike what I witnessed at GM, AT&T, IBM, US Steel, and other giants, they were largely victims of their own success. Hubris replaced imagination. Protecting what they had took priority over being hungry for innovation. Lawyers and accountants ruled. Worrying about the average shopper and her experience on the selling floor was not the topic of Board of Director meetings. To one degree or another, the same could be said for Penney and Kmart, with those two making some especially bad acquisitions, taking their minds off their core business in order to be “cool.” The bottom line was that all three were sick companies and everyone knew it.

Sears and Kmart had boards and leadership which ended up turning control over to either turnaround artists or financial wheeler-dealers. Many did not know or love retailing. For some reason – I’d still like to learn more – Penney’s board instead picked Allen Questrom, a great retailer who had grown up at Federated, to run their company. Wall Street expected a quick fix, but when Questrom told them it would take a few years, Penney’s stock and bonds collapsed.

But neither Kmart – which later went bankrupt and then merged with Sears – nor Sears made good on expectations of rebirth. Penney, on the other hand, achieved Questrom’s goals and the company’s securities rebounded. So when you read in the press rush of the last week that Penney is a sick old company, it’s not nearly as sick as it might have been. While plenty remains to be done, Questrom and his successor Mike Ullman have done an amazing job. Taking over Penney today is not like taking over Kmart in the 1990s – a thankless, likely hopeless job which ruined the track records of more than one “great retailer.”

Despite Penney’s relative strength (compared to Sears and Kmart), it’s still been a tough road. The soft goods and apparel business is tougher than ever, with everyone from the above-mentioned competitors to the specialty stores competing, along with TJ Maxx, Marshall’s, Wal-mart, and Target. But the fiercest head-on competitor to Penney’s is Kohl’s, which came blazing out of Milwaukee with aggressive innovation.

Note however that, instead of staying wrapped up in old mall locations, Penney has closed their weak old stores and opened new stores along the highways with at-the-door parking so they can compete more effectively with Kohl’s. Penney’s is not a fast-asleep giant.

Ron Johnson

In this context, let’s step over and look at what Mr. Johnson has been doing all through these same years.

He gets out of Harvard Business School and skips McKinsey and Goldman and all the other big buck opportunities to go to work in retailing. You gotta love retailing to make a move like that. He spends almost 20 years rising through the ranks of Target – no better place to learn the trade – and rises to be the head of merchandising – the biggest buyer of them all.

He then, as I understand it, has several job options – totally understandable – but takes up Apple’s challenge of creating a chain of computer stores. In my nearly-perfect 2001 book (https://garyhoover.dpdcart.com), I was pessimistic about this idea. Find me a computer company that had figured out how to run stores. Find me any computer store that worked, even if run by veteran retailers. Do you remember the Gateway stores, Computerland, or CompUSA? Making consumer electronics and running a bricks and mortar retail store are really different businesses, and each is hard enough in its own.

But I did not know the history of Ron Johnson. Now I do.

You’ve already heard the next part of the story. Apple stores now average over $25 million per location, roughly equal to Macy’s much larger and more expensive-to-operate units. Most customers love them. They elevate the retail experience and they make money hand over fist. Johnson has made hundreds of millions (reportedly over $100 million in one day!) on his Apple stock options. Good money for a retailer, even one with a Harvard MBA. Credit Ron Johnson’s retail licks combined with Steve Job’s gadget ingenuity. Taken as a whole, few other tech companies in history have understood and served customers so well. (Maybe IBM from the 1930s to the 1970s.)

What the Future Holds

No one can know the future with absolute clarity. Read Peter Drucker’s book Innovation and Entrepreneurship – still the best book on those subjects – and you will see his praise for Apple. But that Apple was the one that would be long forgotten by now if it had stayed under the same management. So even the wisest, most astute business scholars cannot know how companies and managements will change, for better or for worse. With that caveat, here’s where I would place my bet:

Penney, even without Ron Johnson, is a lot less sick than Wall Street thinks. They have great locations, they have lots of new stores, they have a big customer base, they have links to manufacturers of all the key types of merchandise they sell. They are behind Kohl’s (in hunger and in revenue), but only slightly. (Unlike Kmart which is eons behind Wal-mart, the reverse of the 1973 situation.)

Ron Johnson is not just about Apple. He is about Target. He spent almost twice as many years at Target as he did at Apple. He learned the trade from some of the best merchants in the last 100 years. He then took Target to an even higher level – one from which it may not have advanced much – as the chief merchant.

At Apple, he had the chance to try his licks on a clean-slate startup chain. He worked with a likely-imperious boss but somehow pulled it all off. He had the hottest merchandise in the world to sell, and that was a big plus. But not just anyone could have done this job: the folks who control Sears and Kmart would likely have bungled even the Apple opportunity. Johnson taught and led, but like any great teacher, he also learned from this experience.

At JC Penney, for the first time in his life he will run a giant retailer, he will (unlike at Apple) really run the whole show, and (unlike at Apple) he will have the freedom to find the best suppliers and most exciting merchandise. On top of that, he knows from his Apple experience all about making things fun for the customer.

Even Kohl’s and Macy’s are not turning the world on its head in terms of (1) exciting merchandising, (2) finding new products, and (3) a dramatic in-store experience. Target is still the best on the first two. Apple speaks volumes about innovative new products, and is way ahead of everybody, including Target, in #3, the in-store experience.

The bottom line is that Johnson can now get back to business. Away from the narrow focus on a small product line connected with a single brand. But by doing both the Target track and the Apple stint, he understands the broad line department store business and he understands the intensity of running a great specialty shop. Most important of all, he loves retailing and is entrepreneurial: still willing to walk away from money in the bank to create something new and dynamic. (See a video about my definition of entrepreneurship at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gs-xNwGzMvA).

And, contrary to what you might read, he’s not joining a shipwreck. Penney is perhaps adrift in the ocean, but maybe in a better position for this kind of change than any other big general merchandise retailer. No one knows how it will all turn out, but this is one time where I think Wall Street (in the form of Pershing Square Capital Management’s William Ackman, a huge Penney stockholder) probably has it right when he says, "The market says the guy we hired is worth $1.2 billion. The market is wrong; he’s worth way more than that."

|