In 1941, Fred Lazarus, Jr., had some time to kill in Houston. He had come to visit his son Ralph who was serving in the Army at nearby Ellington Field.

Twelve years earlier, Lazarus and his family had united their family-owned Lazarus department store in Columbus, Ohio, with the larger and more profitable Abraham & Straus of Brooklyn and Filene’s of Boston to form Federated Department Stores. While each continued separate management under the old leaders, the three figured they might better weather regional economic ups and downs by holding stock in one larger enterprise. The “Lazari” also contributed their store in Cincinnati, Shillito’s. One year later, in 1930, Bloomingdale’s on Manhattan’s Upper East Side joined the group. Fred, Jr., was CEO of the company.

The city of Houston, with a 1940 population of 384,514 in 1940, was the second largest city in the south, after New Orleans. Future giant Atlanta was at 302,288; Dallas 294,734; Miami 172,172, and Phoenix below 90,000. These markets were tiny compared with New York City’s 7.5 million, which could support higher revenue stores.

Like any good merchant, Lazarus could not resist checking out the Houston retail scene, in those days centered on downtown. He soon discovered that the leading store, Foley’s, was only doing about one-third the annual revenue of his Shillito’s store in Cincinnati, which was only slightly more populous than Houston. Lazarus could see that Houston was booming, and he sensed that there was a big opportunity here.

He tried to buy Foley’s but was rebuffed. He let them know he was going to build a store on his own to better serve the market, and began the process, but Foley’s owners changed their minds. After four years of haggling, Federated bought Foley’s for $3.6 million in 1945. The company then spent $9 million building a revolutionary new store in downtown Houston. The store began a new era in department store design, eliminating outside windows above the first floor, when Lazarus realized it would be better to have stockrooms around the perimeter and keep the selling floor in the center of each floor, where it did not need windows. Air-conditioning costs were reduced. Famous industrial designer Raymond Loewy designed the striking interiors. Foley’s new downtown Houston store opened in 1947 to a crowd of 200,000. First day sales were 2.5 times the best Foley’s had ever done.

This would not be the end of Lazarus’ ability to look at the numbers and see the future. In 1951, Federated bought Sanger Brothers, a leading Dallas store, for $4.25 million. A few years later, Lazarus bought another Dallas store, A. Harris, combining the two into Sanger-Harris, which went on to become the leading store in the Dallas-Fort Worth region. In 1956, he bought Miami’s leading store, Burdine’s, for $18.5 million. In 1964, Federated paid $233 million for the much larger Bullock’s of Southern California, which also owned the upscale I. Magnin. In every case, Federated backed the new acquisitions with better systems, executive training programs, and most of all ambitious expansion plans, building branches across the southern United States. (Today Federated, now renamed Macy’s, continues to operate across the US.)

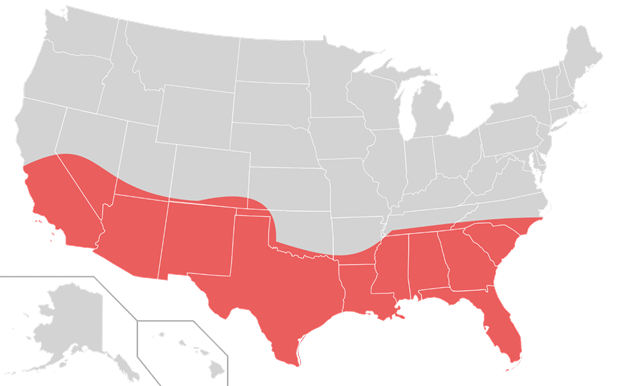

Thus, over a period of 20 years, Federated became a key competitor in growth markets across the sunbelt – a term that was not even coined until 1962. While the data that led to these decisions was readily available from the US Census, how many other companies really understood the implications? What were those implications, and how long did it take them to play out?

In the 1970s, I served as a securities analyst in New York covering the department store industry. My employer, Citibank, was one of the largest holders of Federated stock. I then joined Federated as a buyer for Dallas’ Sanger-Harris, and later worked in competitive analysis for competitor May Department Stores. As a result, I have substantial personal files and industry estimates on revenue and profitability by city. Here is what that data tells me.

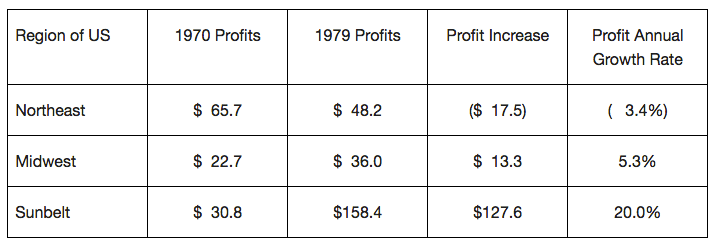

By 1970, after Federated’s raids on the sunbelt were largely complete (they later bought Atlanta’s great store Rich’s). Even at that late date, massive operating profits were flowing from their Northeastern and Midwestern stores. By 1979, only 9 years later, the picture had changed radically. The estimated data (excluding Rich’s) in this table is in millions of dollars.

If Federated had remained focused on the Northeast and Midwest, profits in the 1970’s would have dropped by $4 million dollars. Instead, they rose by over $120 million. These are huge numbers for a company of that size at the time.

This performance resulted from visions first seen 30 years earlier. By a man who studied his numbers, studied opportunities, and acted on his findings. Does your organization study the numbers and know what to do about them? Do you have this kind of foresight?

Please add your thoughts and comments here on LinkedIn.