Mr. Trump seems obsessed with closing that “awful $800 billion annual trade deficit.” He is not alone, with everyone from trade unions to democratic socialists also raising red flags.

Unfortunately, our system of politicians, special interests and favors, and election cycles give little incentive to long-term and big picture ideas, policies, and legislation.

Take the “$800 billion” gorilla of the trade deficit. And apply three key analytical rules in trying to understand how the world works and therefore how to make it better for everyone:

1. Always start by expanding the scope of your exploration. Stand on an even slightly higher hill among the many observing the world, and you will see so much more. Think a move ahead, a mile further away, or a year beyond where others are thinking. Understand the system of which this issue or question is a part. Thinking more broadly is the key to wisdom.

This ideal is related to two “operational” or applied thinking rules:

2. Everything I see or think about is a part of something bigger. This applies to virtually everything in our lives: from a single object to the global political economy, whether tangible or intangible, from farm and factory production steps to philosophical systems and art. Everything a component, subset, subclass, species, type, or genre of something bigger.

3. Likewise, everything I see or think about is made up of components. What are they and how are they inter-related?

Understanding what is “without” and what is “within” any thing you are interested in multiplies the power of whatever you learn by knowing the thing itself. Clear thinking accrues to those who understand the context.

Knowing how to turn on & use your smartphone is the level most people think at. Knowing its critical parts & how its innards work, even at the first level, adds breadth. Knowing how Mobile social media works, how the Internet works, and following innovation, products, and companies yields an understanding of the overall system, of which the smartphone is just one part.

So let’s really think about that huge number, $800 billion.

What’s it part of?

In 2015, the United States had net exports of goods (exports minus imports) of $762.6 billion. This is the “$800 billion trade deficit” number many are upset about. But by looking only at goods, not services, we forget that in 2015 the US was a net exporter of services of $262.2 billion. America’s transportation and travel industry, financial and business services segments, and many other industries are important factors in the global economy. Since 2007, this net services exports number has more than doubled, while the trade deficit on goods has actually declined (from $821 billion). Taken together, our net trade deficit, of both goods and services, was $500.4 billion in 2015, not $800.

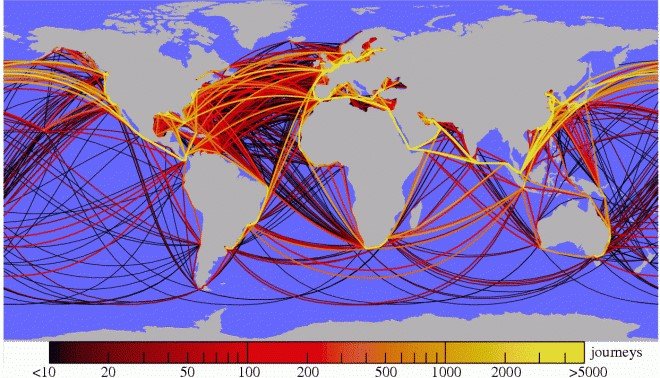

But focusing on net numbers, as talking heads often do, limits our view of the big picture. The gross trading activity between the US and the world is far larger. Total US imports of goods and services in 2015 was $2.76 trillion, and our exports were $2.26 trillion. Taken together, total trading activity was a $5 trillion “industry” last year, or about one-quarter of our total economy. One study by economists found that in 2000, 47.9 million US workers worked for companies involved in international trade, or 41.9% of the US workforce. 75% of these workers were at companies that both imported and exported.

It is easy to forget or gloss over the fact that our importers and their products are critical parts of the US economy. All those Toyota and BMW dealerships and the vast support and transport network required to bring the goods to American consumers employ millions. The cost savings for everyone in America is huge. Apple would not be Apple without Chinese and Taiwanese factories. When one shops at Ikea, drinks Lipton Tea, or buys Shell gasoline, they are part of the global economy.

It should not be so easy to forget that increasing tariffs or barriers on imports almost certainly triggers reactions from the other countries – “trade wars.” Our $2.3 trillion worth of goods and services exporters could be severely hurt, costing even more jobs.

I believe we should focus more on the $5 trillion “big picture” rather than the net of a “measly” $500 billion deficit.

This argument is supported by most economists. The ones I trust the most tell us that the deficit in itself is not a bad thing: the dollars that go abroad are exchanged for things we would rather have than the money, or we would not make the exchange. And that most of those dollars flow back into the US as investments, such as Samsung’s $5 billion+ capital investment in Austin facilities alone.

The global economy is in many other ways connected. In 2015, Americans and American companies received $776 billion in income from investments in other countries, and foreign companies earned $582 billion on their investments in the United States.

For all these reasons, many bi-partisan politicians have long supported free trade as being good for America, including Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and until recently Hillary Clinton, Mike Pence, and Tim Kaine.

Most economists believe NAFTA has been good for those involved, strengthening North America’s competitive power around the globe. While trade agreements may need to include worker, environmental, and other protections, the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) which President Obama has been pushing hard appears to make significant improvements over prior trade agreements. Negotiated over seven years, many nations have made compromises in order to sign up. Some of those who rail against it keep mentioning China, which is not a party to the TPP.

There is no question that any kind of trade, progress, and innovation “dislocates” workers. This process is not new, and not caused only by world trade. Cyrus McCormick invented the reaper, reducing the need for farm labor. Others invented the calculator which killed off slide rules. I remember as a child the frequent home visits of “TV repairmen” – now long gone. My hometown of Anderson, Indiana, went from 27,000 General Motors workers to zero in the 1980s and 1990s.

The challenge here is not one of cutting imports and fighting global trade wars, but of figuring out ways to provide a safety net for workers and to make sure our great American labor force has the skills and talents appropriate to ever-changing demand and technologies. Bringing steel production back to the US is not a realistic option – that “train has left the station.” And substantially more steelworkers are not what America needs to be a vibrant competitor for the multitude of opportunities that our global markets present.

I would love to see your thoughts here on LinkedIn.