This article was originally published in Fall 2021 edition of the Profectus Magazine.

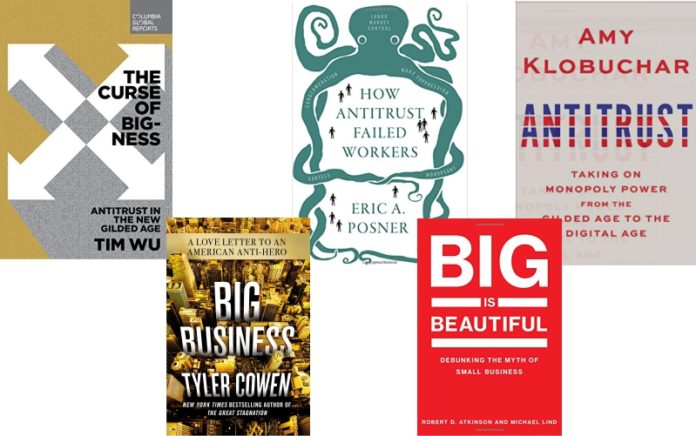

Today, antitrust and the regulation of big corporations are hot topics among Democrats, Republicans, media pundits, and the authors of numerous books advocating and opposing more aggressive antitrust action, especially with regard to Big Tech. The issues revolving around federal regulation of business, antitrust, the Department of Justice, and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) are at the heart of my own interests.

I grew up in a General Motors factory town. My teachers’ inability to tell me much about this company, so critical to our local economy, led me to subscribe to Fortune magazine at the age of twelve, fifty-eight years ago. I then embarked on a lifelong study of big and small businesses, including studying economics at the University of Chicago. My area of concentration within economics was industrial organization, the study of monopolies, oligopolies, and antitrust. I have since worked for three Fortune 500 companies before starting my own series of companies with friends, two of which took on industry giants and changed their industries (bookselling and business information).

The bottom line is that I love to study business, especially how companies are born, how they think and behave (for better or worse), how they grow and achieve market share, and how they die.

Having studied hundreds of antitrust cases and observed the ultimate effect of government efforts to regulate competition, my conclusion is that antitrust actions rarely, if ever, have a net positive effect on society. The vast majority of these lawsuits only waste the resources of the government (taxpayers) and the resources of the companies involved.

Even if we assume the best of intentions on the part of regulators, revisiting the track record of past antitrust actions is required to predict what might happen in the future. Several key patterns emerge:

- There is an inability or unwillingness of regulators to accurately define markets, the realms in which companies compete.

- Perhaps ironically, there is an inability of regulators to really understand how competition in a free market works. They do not understand the limits placed on corporate power by consumers or competitors, including upstarts and new technologies.

- The fundamental nature of antitrust action is reactionary. Regulators are consistently reacting to the past rather than having any understanding of what the future might bring and how such changes should factor into their decisions.

Much like today, many of the important antitrust actions of the past resulted from populist concerns about big corporations and their power. At first it was the railroads, then big industrial companies, later chain stores, and today Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google. With public sentiment against these companies, members of Congress and the unelected regulatory agencies get good press by taking them on. Everyone likes a good “slaying Goliath” story (or myth).

At times, bigness alone was seen as evil, even if it was the result of companies making superior products. In recent decades, regulatory and judicial attitudes have shifted to focusing on whether the companies’ actions helped or hurt consumers; bigness alone was no longer seen as evil in itself. Today many are swinging back to the “big is bad” justification for government action. This is an unfortunate trend.

To understand my conclusions, it’s important to briefly look at some cases from history.

The first famous antitrust case resulted in the 1911 breakup of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust, as ordered by the Supreme Court. Rockefeller had gradually achieved an 80-85 percent share of U.S. oil refining. Yet by the time of the breakup, Rockefeller’s dominance was in decline: his share had dropped about twenty points from those peak levels. He also did not control the oil fields themselves and did not participate in the new discoveries in Texas, led by competitors Texaco and Gulf (financed by Pittsburgh’s wealthy Mellon family). Rockefeller also faced steep international competition, especially from the British-Dutch giant, Shell. He was not the leading innovator in marketing (gas stations). And, throughout his empire building, he lowered the price of oil again and again. Also note that the breakup took place before the rise of the automobile and the demand for automotive fuels, which led to the huge rise of the oil industry, including over one hundred competitors.

In other words, the breakup took place when Standard Oil was past its peak and already losing out to the competition. The regulators were looking backwards, not forwards. Even renowned trustbuster President Teddy Roosevelt admitted that he did not think the company should have been broken up. The net result of the breakup was that several large companies, including the future Exxon, Mobil, and Chevron, were created out of the trust, all owned in large part by Rockefeller, his partners, and descendants.

Fast forward to the 1940s, when the trustbusters went after the world’s largest retailer, the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, known to every American as “the A&P.” The company’s great sin was to continually lower prices, lower costs of production, and save consumers money. While A&P was the largest grocery store chain in the nation, they had very large competitors in every region, including Kroger, Safeway, Grand Union, Acme, and National Tea. After years of court fights and great expense, the company received a slap on the wrist. Yet A&P had already peaked, and by the 1960s, was a broken company in steep decline. It no longer exists today.

In 1948, the government ordered the big Hollywood movie studios like Paramount to divest their chains of movie theaters. The companies had become “too powerful.” Yet this action, resulting from years of investigations, took place at almost the exact time that commercial television arose, rapidly entering homes across America. Both the movie studios and the theater chains went into rapid decline. Again, the trustbusters were looking backward, not forward (nor were they even aware of the present, as everyone knew that television was about to burst on the scene).

In this same era, the trustbusters continually pursued Eastman Kodak. Kodak consistently sold at least 70 percent of all the consumer and movie film in America. This was one of the highest market shares ever recorded without government support and complicity (as AT&T had in telephone service and Pan American World Airways had in international air travel). The great George Eastman achieved his market dominance by making a better product, continually innovating, developing a global distribution system with a well-known name and trusted trademark, and by treating his employees perhaps better than any other big American company of the time. After years of trials and great expense, nothing important came of the efforts to stop the company’s power. Yet, ultimately, that power proved to be worthless in the face of new photographic technologies, despite Kodak having been an early innovator in digital photography.

The 1960s witnessed a flurry of antitrust actions.

By the early 1960s, General Motors was selling more than half of the passenger vehicles in America. It was the largest company in the world by revenue, employing over 700,000 people, and the largest taxpayer, paying 4 percent of all the corporate income taxes in the United States. Regulators began to come after GM, its bus and locomotive manufacturing operations, as well as its passenger cars. It was too big, too powerful, too scary. Once again, nothing important came of the antitrust actions, as the regulators did not understand the impact of Volkswagen, Toyota, and Datsun, all of which first came to the States in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Nevertheless, there are indications that fear of being broken up caused GM to lose some of its earlier ambition. Why increase sales if that is going to put your company in danger of being broken up? This reaction may have cost employees and shareholders millions of dollars, and cost consumers new innovations.

The 1960s also saw the big department store chains like Federated Department Stores and May Department Stores slapped with “consent decrees” in which they were banned from buying more local department stores, as they had been doing all through the twentieth century. As a result, in their natural desire for growth (both for stockholders and employees), these companies ventured into fields in which they had little expertise, such as grocery stores and discount stores. Few of those investments turned out well, harming stockholders and employees. The regulators defined department stores very narrowly, only seeing competition as being stores of the exact same type. They ignored such upstarts as Kmart, Walmart, and Target (all founded in 1962) as well as later innovators TJ Maxx, Ross, and Marshall’s. The Gap, Old Navy, the Limited, and other apparel chains also took market share from the older department stores. By the 1980s and 1990s, the regulators seem to have realized their blindness, allowing the department stores to buy out each other without any limits, resulting in most of the industry becoming Macy’s. Today the entire department store industry, as the feds defined it, is a fraction of the size of Walmart or Target.

Perhaps the most famous case of the era, and most relevant for examining tech industries, was the effort to break up and limit the power of International Business Machines (IBM). This antitrust case, like most others, dragged on for years, during which each side spent between $50 and $100 million per year. This was money taken from taxpayers on one side and from stockholders, employees, customers, and innovation on the other side. Millions of pages of testimony were recorded. And, as in the above cases, the trustbusters were looking backward rather than forward. The rise of minicomputers led by Digital Equipment, Data General, and Hewlett-Packard soon challenged IBM, followed by the microcomputer. Nothing important came of the lawsuit, and by the early 1990s IBM only narrowly escaped bankruptcy.

While these antitrust cases made headlines in the financial press, trustbusters also meddled in the affairs of many smaller companies in smaller industries. Such efforts hit close to home when the regulators stopped the company my father worked for, the Indiana Glass Company, from buying another maker of consumer and tabletop glassware, Federal Glass, in the 1970s. Even though the two companies combined would be far smaller than the largest companies in the industry, the FTC thought they would be “too big.” After months of debate, the FTC relented, but it was too late, and 1,500 workers at Federal lost their jobs when the plant closed. In the following years, all these companies were allowed to be swallowed by larger competitors, and the American glassware industry went into decline as it was overwhelmed by foreign competition—a predictable outcome my father could have warned about even before the FTC brought its case.

In the early 1980s, the government went after AT&T, which was in fact one of the rare, true near-monopolies, providing about 85 percent of America’s local phone service and all the long-distance service. Since the early twentieth century, AT&T had appeased regulators by keeping its rates low and offering exceptional service. The company also gladly connected with hundreds of smaller local telephone companies around the nation. But as big again began to be perceived as bad, the company was broken into large regional companies like Bell South and Bell Atlantic. This happened at the same time that a new telephone company, MCI, was beginning to make inroads into AT&T, and just as new cellular technologies were emerging that would change telephony forever. While this breakup may not have done much damage to American consumers, even it was likely unnecessary given these emerging industry changes.

By the 1990s, the company to fear was Microsoft, the same company which played a role in the decline of IBM, but which now had risen to the top of the tech world. Again, years of investigations, millions of dollars, and great human effort were wasted with little outcome. Microsoft soon enough found itself under tremendous competitive pressure on all fronts from the likes of Oracle, Apple, and foreign competitors.

And so, today, the tables turn again, and we are told that Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and others are “too powerful” and must be brought down a notch. Yet none of these companies can force anyone to buy their products, use their services, or work for them. Every customer is making a voluntary decision as to which company to buy from. Every supplier has freedom of choice in which companies they deal with. And no field changes faster than technology and social media—just ask AOL, MySpace, and Yahoo.

In congressional hearings, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos pointed out that his company was still smaller than Walmart, at which point members of Congress rejected his argument, refusing to see Walmart as a competitor for Amazon. To define Amazon’s competitive world as only being eCommerce ignores the reality of total retail spending. The numbers tell us that about 87 percent of US retail sales are still through brick-and-mortar stores, and that Walmart, Target, and others are gaining eCommerce market share on Amazon. The future of retailing has just begun.

Make no mistake, if companies defraud their customers, they should be punished. If companies cheat on their taxes, they should be punished. But beyond such illegal actions, trying to predict the future of various markets and outguess the actions of future competitors and technologies has proven to be futile time and time again.

Rather than relying on backward-looking, reactionary regulators, the only factors that will bring down these companies are new competitors, new technologies, and fickle customers who are always looking for something better. Many observers can already see chinks in the armor at each of these Big Tech companies, or competitors already on the scene and growing.

Corporations have far less power over our lives than the press would like us to believe. Just study the histories of powerful companies, including General Motors, Chrysler, Sears, Kmart, FW Woolworth, JC Penney, US Steel, IBM, Digital Equipment, Westinghouse, International Harvester, Union Carbide, RCA, MGM, Pan American Airways, and many others. No company can force you to work for them, supply them, or buy from them. Only the government has the power of force. Companies perish when they fail to fulfill a purpose for society.

There is always a Toyota, Walmart, Tesla, Netflix, or TikTok ready to take your company down. Free markets made up of voluntary buyers and sellers, not meddling bureaucrats and expensive lawsuits, dethroned those formerly great companies and will undoubtedly do so again.

This article was originally published in Fall 2021 edition of the Profectus Magazine.