|

Continuing each Monday another excerpt from my 2001 book, which can be purchased as a PDF for $10 here: https://garyhoover.dpdcart.com.

Our understanding of the world is best served by connecting change through time and change through space. That is, how is the world changing as we proceed into the next century? Understanding where one stands in time and space is critical to building a successful enterprise, critical to understanding our operating environment. Especially important is understanding the biggest and longest-term factors at work – the evolution of the earth and where it is today. This is where history and geography intersect, where change through time and differences around the globe meet.

The more I study these long-term trends, the more I conclude that the facts are extraordinarily positive. So I call this overview “The Rise of the World.”

Wealthier and Wealthier

Over the long term, the world – the whole world – is getting wealthier and wealthier. How do I define wealth? I mean the total accumulation and dispersion of the assets that are most important to humanity – lifespan, health, education, food, clothing, shelter, safety, peace, culture, art, music, transportation—every worthwhile asset from hamburgers to Rolexes, college classes to Hollywood movies, clean and well-heated apartments to five-star hotel rooms.

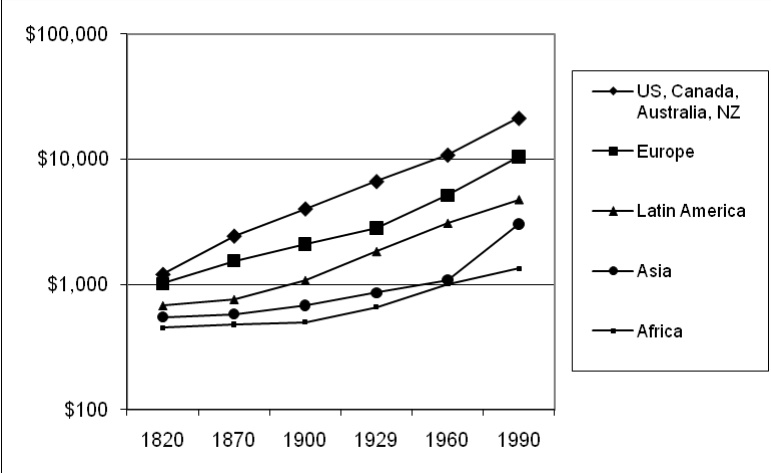

In pursuit of these varied goods, we are all climbing the same hill, a shared hill, from caves to the future. Most organizations, enterprises, and societies are either growing or dying at any given point. In aggregate, the world’s nations are growing, in multiple dimensions, as we climb the hill of wealth. The following graph is a snapshot of all of us climbing up that hill, using Gross Domestic Product per capita (GDP) as a measure of the wealth being created. (Note: The “Western Offshoots” are the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.)

Long Term GDP Per Capita Trends (Adjusted for Inflation)

As we watch the world progress, we see things move forward in small increments: from black and white televisions to color, from propeller airliners to jets, from 16-bit microchips to Pentium processors. But we rarely stand back and look at where we have really come from.

It would be hard to think of a more important measure of wealth than lifespan. Based on available records, primarily English, European lifespans hovered between 30 and 40 from the 16th century through the 18th. Lifespans in England and France began to break through 40 in the mid-1800s. By the end of the 19th century, they were on a steep upward curve toward today’s 70s. A similar curve has taken place in China since World War II. These countries are representative of their neighbors.

The rise in lifespans has been due to many factors: a decline in accidental deaths, canning and other food-processing procedures that reduce contamination, the general availability of safe water supplies and other improvements in sanitation, advances in health care (especially in dentistry), and innovative pharmaceuticals. The rise has been especially great among women (who do not die in childbirth as often) and children (who live to adulthood more often).

While life expectancy may be the single most important measure of wealth, it is also important to consider the quality of our lives. Worldwide education levels and literacy keep rising. Pollution levels, which are still high, particularly in many poorer countries, are coming down. (Los Angeles today has cleaner air than at any time in the past 30 years; previously unseen species of fish are spawning in New York’s Hudson River.) Total world production of and access to works of film, music, and art are at record levels. The world’s great museums are drawing more visitors than at any time in history.

I am focusing on non-financial forms of wealth both because they are more important to our ultimate satisfaction and because they are sometimes forgotten when we talk about wealth. But it would be equally regrettable if we forgot the inextricable link between financial wealth and cultural and physical wealth. Nations with high incomes can more readily afford clean air, clean water, great museums, and medical clinics in every neighborhood. Great art collections and great universities are often founded by wealthy individuals with generous spirits. More profitable corporations are more likely to give to organizations that work to help the homeless, the illiterate, and the abused. In short, all the forms of wealth are intertwined and tend to come together. This is especially true when at least some of the wealth is spread among a large middle class.

I do not mean to appear Pollyannaish — there is still widespread poverty and many other forms of evil in the world. As recently as 1994, the government of Rwanda or its affiliates murdered between 700,000 and a million of its own citizens. Those victims who could afford to do so bribed their attackers with money so that they would be shot rather than hacked with a machete. The world has probably not seen the last Hitler, Stalin, or Pol Pot.

Furthermore, even in the most prosperous nations, there continue to be pockets of poverty and deprivation. There will continue to be economic cycles, and in the downturns people living near the edge of poverty are likely to slip backward into true want. And there will always be accidents and acts of nature which cost the lives of millions and bring suffering to even more.

It’s the nature of progress that it generally consists of two steps forward, one step back. Sometimes we seem to take two steps back. But we should never lose sight of the long-term trends, the direction in which humankind has been heading for at least the last two centuries. It’s the direction which all of us on earth are heading – up. In fact, the largest gains often accrue to those who started out the furthest behind.

The next table shows recent trends in life expectancy (measured at birth, reported by the World Bank). The wealthy, poor, and very poor countries listed in the table are representative of many of their neighbors. Even in China, where an estimated two million people a year die of lung cancer alone, the 7.8 year increase in lifespan matches that of the best “rich” countries.

LIFE EXPECTANCY AT BIRTH

1970 1997 Increase in Years % Increase

RICH NATIONS

Japan 72.2 80.0 7.8 10.8

Switzerland 72.9 78.6 5.7 7.8

United States 70.7 76.7 6.0 8.5

MIDDLE NATIONS

Mexico 61.1 72.2 11.1 18.2

China 62.0 69.8 7.8 12.6

Thailand 58.3 68.8 10.5 18.0

POORER NATIONS

India 49.1 62.6 13.5 27.5

Bangladesh 44.2 58.1 13.9 31.4

Haiti 47.4 53.7 6.3 13.3

Nigeria 42.7 50.1 7.4 17.3

These trends don’t just happen by themselves. It takes work by millions of intelligent, generous, and hardworking people, good leadership, and active organizations. And it goes without saying that the positive trends have not reached all peoples equally – some African nations like Ethiopia have seen very little improvement in this era. As of 1997, the average life expectancy at birth in sub-Saharan Africa was only 48.9. But there is ever reason for hope, for high expectations, and to keep working hard to achieve further improvements.

The fact that the countries that started further behind have often gained the most is in large part the principle of convergence at work. That is, there is a natural tendency for values to move towards the average. And when the average is rising, those who are furthest behind are often going to rise faster than others.

This same mathematics tends to affect every other group that started behind. For example, the primary beneficiaries of what I call the rise of the world are women. In terms of lifespan, education and literacy, power and participation in politics, and relative economic status women have enhanced their position dramatically worldwide. And children are coming right along with them. In many societies, little girls have historically been the lowest on the totem pole, getting less schooling, less access to inherited wealth, and less of everything else. This is one population segment that will benefit the most if we keep moving things ahead. Already, women in college outnumber men in college in about half the world’s nations, especially in the middle-income and wealthy nations.

At the same time that most trends are clearly positive, particularly among the poorest countries, it is important to realize that the rate of progress of particular nations is largely under their own control. That is, countries get rich or fail to do so largely as a result of their own actions. Consider, for example, the six countries shown in the next chart, which were economic equals only one hundred years ago.

GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT (GDP) PER CAPITA IN CONSTANT (INFLATION-ADJUSTED) DOLLARS

Of course, there are many factors that affect how successful each nation is and how fast its people are enriched. These include the broad global factors of success, including democracy and technology, that I will cover in a few pages. But one other dimension that we cannot forget is the quality of leadership. If you study the nations of the world throughout history, it is a relatively rare and historically recent phenomenon for leaders to make serving their citizens a high priority.

In other words, most kings, emperors, and generals had as their first priority defending their borders or conquering their neighbors. The next priority was making their family and friends and all those who helped put them in power and keep them there comfortable. This applies to the Janissary soldiers of the Ottoman Empire in the seventeenth century or the executives of United Fruit Company in Central America in the early twentieth century. Taking care of your friends has always been high on the priority list of most political and economic leaders. As I write this, the citizens of Indonesia are rioting in the streets as the political leadership tries to sort out the legacy of President Suharto, who did many great things for his people but also made sure his friends and family had well-lined pockets in the process.

|