|

Continuing each Monday another section from my 2001 Book, Hoover’s Vision. Today we go more deeply into the importance of studying history in order to know the future, of understanding how things change through time.

“The further backward you look, the further forward you can see.” – Winston Churchill

In the previous chapter, we looked at some of the key trends currently at work in the world. But understanding change through time is most helpful when you get in the habit of doing it every day, when you look at each event and try to put it in historical perspective, when you look at your own company, non-profit organization, or industry with your “time-sensitivity” turned on. The following pages contain techniques you may be able to use in developing your own time-sensitivity.

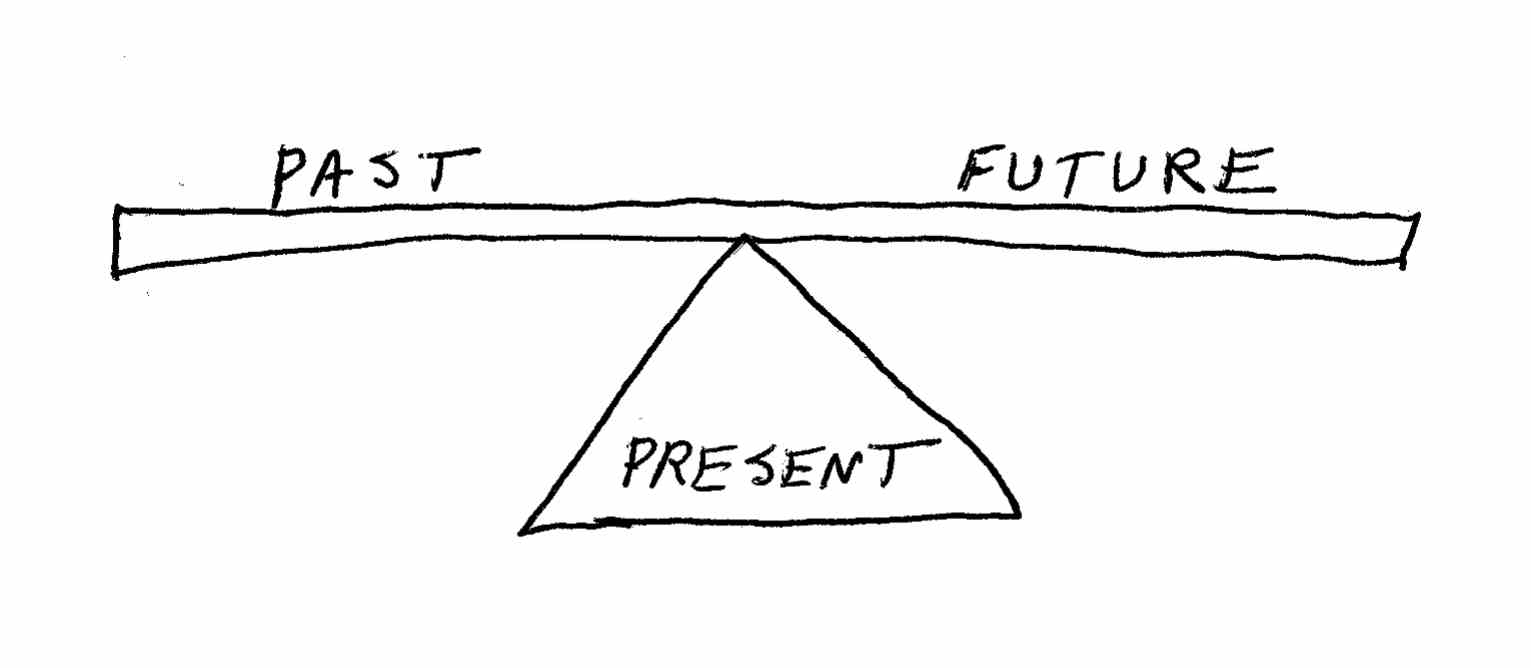

First, remember that you cannot know where you are going unless you know where you are coming from. It is as important to be retrospective as it is to be prospective and introspective. We must seek balance, looking before us and behind us as well as inside us. I have seen many Wall Street analysts’ reports that show sales and profit projections for the next five years, but show only one year of history. Such analyses are likely to be seriously flawed. An image that may help you in remembering to maintain your “time balance” is shown here. The present is the fulcrum of the seesaw of time.

The Evolutionary Mindset: Watching Change Through Time

“History may be divided into three movements: what moves rapidly, what moves slowly, and what appears not to move at all.” – Fernand Braudel

Of course, history is easier to recognize and analyze in retrospect than while it is happening all around us. Hence the expression, “20 / 20 hindsight.” But there are ways of observing history in the making and thereby gain a quicker and more accurate understanding of change than most people enjoy.

The first step in watching history as we live it is to separate what is changing from what is not changing. Experience suggests that most aspects of human nature change very little: the need for food, shelter, and other basic requirements of life; the desire to make a better life for the next generation; the importance of honor and reputation; the wish to love and be loved. On the other hand, technologies and artifacts of civilization – from cars and music to houses and clothing – are changing all the time. There are also human attitudes that are changing over the long term—not all at once, but gradually, one society or sub-group at a time. In general terms, we can say that the human race has changed its attitudes and practices in regard to such topics as slavery, education for the masses, the rights of women, the importance of freedom and democracy. In each of these categories, the dominant world view held today is significantly different (and most would say improved) from that of five hundred years ago.

Sometimes unchanging human nature intersects with ever-changing artifacts. My grandfather thought my dad was nuts for liking Louis Armstrong; my dad thought I was nuts for liking Mick Jagger. I suspect that, if I had a son, he would like Eminem – and I’d think he was nuts. Yes, styles of music have changed, but the fact that dads think their sons are crazy has not.

The leader of an enterprise must deal with all of these aspects of human culture: artifacts, technologies, customs, attitudes, beliefs, preferences, and many more. Most of the “things” that an enterprise deals with are changing, some slowly, some quickly. We humans are naturally good at noticing things that move fast – action movies, horse races, basketball games. Evolutionary research suggests that this is a trait of perception that developed over time for excellent adaptive reasons: early humans on the African savannah needed above all to be quick to see and react to the sudden movements of an attacking predator, rather than the slow movements of branches in the wind or water in a stream. Thus, our senses are attuned to seeing rapid change while ignoring gradual changes. It takes more work to watch things that move slowly – clouds, demographics, long-term trends in industry, history, or culture.

Yet most things are evolving. Seeing things as evolutionary is an important change-watching skill, one that applies even to things that seem not to move at all – in fact, especially to things that seem not to move at all.

One excellent example is language. You may assume that the English (or other language) you learned at your mother’s knee is the same English you use today and will use until the day you die. But our language evolves every day. Try communicating in business today and not using words like dotcom, Internet, or cell phone. Young people are especially adept at integrating new words into the language, from rad to phat. No matter what your personal tastes in music may be, you know what words like rap and hip-hop refer to. And as our world becomes smaller and our culture more diverse, languages increasingly intermingle. You probably know the names of a dozen popular Mexican foods and can understand Hasta la vista and Cinco do Mayo without thinking about them. Asian-American terms are sure to blossom in coming years.

Over the very long term, the changes in language are enormous. Englishmen who spoke the language of Shakespeare would have difficulty understanding the English our great-great-grandchildren will use. There was a time (only some fifteen centuries ago) when English did not exist, and there may be a time in the future when it no longer exists, a dead language like Sanskrit or Sumerian, preserved only in whatever books or other written artifacts survive.

Sometimes you have to work hard to see evolutionary change. My parents made their first trip to New York when they drove from Indiana to attend the World’s Fair of 1939. I made my first trip to New York when my parents drove our family from Indiana to attend the World’s Fair of 1964. The tradition of enormous world’s fairs started in Europe and peaked with the turn-of-the-century fairs in Chicago (1893) and St. Louis (1904). At these fairs, millions of Americans were introduced to cultures from around the world, to “foreign” religions, and to the newest marvels of science. Even some of our favorite foods, from the ice cream cone to iced tea, were first popularized at world’s fairs. Enterprises used them to showcase their visions of the future.

A world’s fair visit was an eye-opening experience for a 13-year-old kid. But over the years, the power and popularity of world’s fairs has declined. While cities occasionally still hold fairs in an effort to draw tourists, no recent fairs have enjoyed the attendance or success of the great fairs of the past. With my fond memories of 1964, I began to mope about their decline. But then I realized that the fairs were not gone. They had just morphed into other forms. What is Epcot at Disney World but a permanent world’s fair? Our society had become rich enough that we could afford not just one fair every five to twenty years, but an ongoing fair, open all year round. This trend is further manifested in the worldwide growth of science, technology, and natural history museums. But seeing the link between world’s fairs and Disney World was not obvious. One had to look behind their structure to recognize their underlying function, their essence.

It is important to take an evolutionary viewpoint, whether we are looking at something as fundamental as the English language or as specific as the fate of world’s fairs. Every industry, every company, every non-profit enterprise is evolving. Every consumer need or desire, from the need for food to the desire for entertainment, from insurance to transportation, is unfolding over time. We are aware of the latest startup company, we know the hottest trend. But are we looking for how things have changed over a 10, 20, 50, or even 100 year time horizon? And therefore how they might change when we look that far into the future?

|