|

Each Monday I post the next section of my 2001 book, which was originally called (by the publisher) Hoover’s Vision but which I have now retitled The Art of Enterprise. I have posted over half of it already; click on the “Monday” column to see all the prior sections. The entire book can be downloaded as a PDF for $10 at https://garyhoover.dpdcart.com

.

One detail at a time

“God is in the details”–Traditional saying, made famous by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

A couple of years ago, there was a lot or malarkey going around that you could build a brand overnight. People pointed to Amazon.com (which was built quickly, though not overnight) and figured they could run a few ads on the Super Bowl and become a household word. However, unless they wanted to be known in every household as a laughingstock, this did not work.

The reality is that brands and reputations are built very very slowly, one customer at a time, one transaction at a time, one experience at a time. All the ads in the world will not tell as many people about your enterprise as their friends and relatives will. And their friends and relatives will spread your reputation, good or bad.

Building your business, serving people, depends first and foremost on paying attention to details. When I was in the book business, I would often visit the two chains that then dominated the industry – B. Dalton and Waldenbooks. In any given year I might find the stores of one chain terribly messy, with books all over the floor. While a first reaction might be to say they had bad store managers, it was more likely they had bad management. Management that was too busy in retreats or meeting with lawyers or accountants or each other to hang out in the stores. When I go into a Target store, I can tell from the incredible attention to detail that the CEO of Target lives in his stores. When I tour Disney World, I can tell that management at the very highest level cares about every detail of the parks.

An acquaintance told me of being interviewed by Microsoft. They had flown to Seattle the night before the interview. In the morning, the Microsoft person asked, “how was your flight? Is the hotel okay? What did you think of the alarm clock?” What did you think of the alarm clock!! Microsoft asks questions like this one because they want to know, “Do you pay attention to details? Do these things matter to you?”

At the other extreme, when I last shopped for a new car, in 1993, I took a look at the new Cadillacs. Here was a car with a great transmission and a great engine, but no lower back (lumbar) support (standard even on cheaper Japanese cars) and no good place to store coins (don’t they have parking meters in Detroit?). Until some of those engineers get out and live in one of their cars, I don’t think I’ll buy one.

Amazon is seen as a great company for building its brand, and revolutionizing the way books are sold. But anyone who has spent lots of money at Amazon (as I have) knows that this company is built on nothing fancier than inventory availability, coupled with outstanding, detail-obsessed customer service.

I went into a beautiful new retail complex in San Francisco called Metreon. It’s a brainchild of Sony and is anchored by one of their product showcase stores. I admired the beautiful fixtures and the plentiful, helpful staff. I saw all the latest that Sony had to offer. I selected one of their little digital pocket recorders so I could record ideas when I travel. I picked the most powerful one they made. The plentiful clerks told me they didn’t have any in stock. I asked, “Where can I find one?” They suggested the Circuit City store two blocks away. I went there. No one knew about the Sony units, and I bought an Olympus recorder instead.

All that beauty, all that investment, but no one was into inventory control.

I had heard from my friends that Singapore Airlines was the best airline for business trips to Asia. They always flew business class, so I did the same on my first trip. But a few years later I was flying coach and found out what really separated this airline – they treated you as well in coach as other airlines did in first class. Even the food and video system were outstanding. Unlike some US carriers, you didn’t overhear flight attendants joking about having to work “the back of the plane where the Clampetts are.” (“Clampetts” is an unflattering airline term for the non-frequent-flyer masses, taken from the old Beverly Hillbillies TV show.)

How easy is it to open your package? How strong is your shopping bag? How far is it from the parking lot to the door? How wide are your aisles, how high are your shelves, how slick is your floor? Can people understand your instructions? Can they read the labels on the buttons on the electronic gadget you make? How will our aging population like your latest innovation? How simple is your credit application? How complex is your voice mail system? Do your web pages download fast? Do they print out on a single page of paper?

Are you willing to make sacrifices for the benefit of the customer? Most convenience stores and fast food restaurants profit greatly from “selling their soul” to either Coke or Pepsi. So why did 7-11 opt to offer both products in its fountain, running an ad campaign saying “It’s your choice” and boldly going where no one else would go? After years of drug stores telling themselves, “Let’s keep people waiting 20 minutes for prescriptions, and put prescriptions at the back of the store, so people will buy more,” why did Walgreen’s break rank and start putting drive-through prescription windows in every store they could? Does your organization have this kind of courage?

I recently saw an article about the debate in churches as to whether the pews should be hardwood or softened with cushions. Some ministers and priests claimed that it was not right to break the tradition of sacrificing comfort. How many souls will they save if their churches are empty?

Details are everything. There is nothing in the way you deliver your product or service to your customers that does not matter. The CEO’s desk doesn’t matter, the corporate jet doesn’t matter, the latest PowerPoint presentation doesn’t matter unless it somehow makes life better or more interesting for your customer.

A Hearty Story

Perhaps my favorite illustration comes from an unusual company called Build-A-Bear Workshop. An old friend of mine, Maxine Clark of St. Louis, started this company. A few years ago she called me up and said, “I am thinking about leaving the world of big retail corporations and starting my own store. I wanted to see what you thought of my idea. I want to have a shop where people can come in and build their own teddy bear.” I think I told Maxine that it sounded like a small market to me, I didn’t know if it would work, but wished her luck.

Next thing I know, she has 20+ stores (50+ by the time you read this) and is the talk of the industry. So I figure I better get into one of her workshops and see what I had missed in my initial take on her business idea.

I went into the store and found a fascinating process that totally involved kids or their parents. You choose the body, the clothes, and even a pair of eyeglasses for your bear. You stuff it. You choose its name. You go to a computer and print its birth certificate. (Which is always on file, so if your bear is ever lost and returned to one of the stores, they can find you). I was getting pretty excited, realizing how much more involved the concept was, how much more involving it was, than I had ever imagined.

But then I came to the heart department. Here, you chose one of a variety of hearts. The heart goes inside the stuffing, never to be seen again. Why on earth would any rational person want to put something in there, pay good money for it, that no one would ever see? Because this was not about rationality, this was about the total experience of creating your own Teddy Bear. And my friend Maxine (now Chief Executive Bear) and her colleagues had felt that no detail was too small to pay attention to. Certainly not the heart of your bear.

The Value Formula

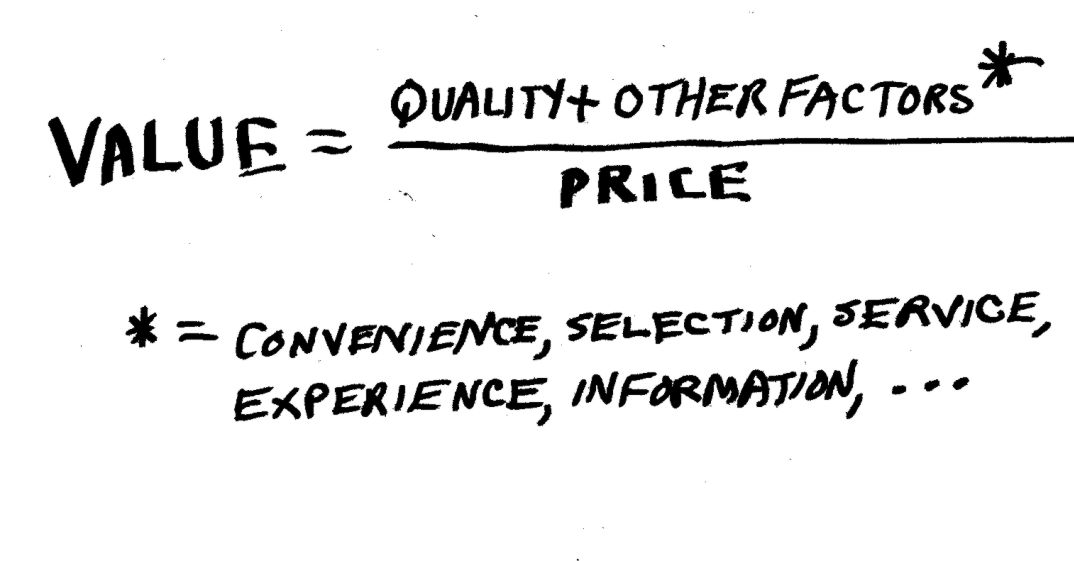

Let me close this section with a quick review of what really does matter in any product or service. Unlike what some believe, it is not the price, it is not the quality, it is not service. It is the total package. I call it the value formula, which looks like this:

Again I go back to the airline industry. I was at a conference where Continental’s Bethune sat on the dais with Southwest’s Kelleher. One of the most interesting questions posed was “Why has Southwest been so successful, while all attempts to copy it have failed?” Kelleher gave many of the reasons I have already described, such as no frills and happy employees. But Bethune, looking in from the outside (and running one of the airlines that had tried and failed to copy Southwest before his arrival) had a different take. He said, “Everyone looks at Southwest and thinks the secret is low fares. They ignore the on-time record, the lack of lost bags. People first and foremost want safe, reliable air travel.”

As you have probably gathered, I admire Wal-Mart as much as anyone. But one sad side-effect on the rest of the retail industry has been an obsession with price. Low prices, which is indeed the Wal-Mart mantra, is only part of a successful formula. The role it plays depends on your store and your customer. Wal-Mart’s cost cutting carries the corollary that the stores have to be pretty bare bones. At one point there was a huge wave of sporting goods superstores that spread across America, including Austin. These companies took something as exciting and evocative as athletics and stripped it of all its appeal, adopting Wal-Mart style flooring, lighting, and overall plainness. Within a couple of years, most of them were closed.

By contrast, Target realized that the best way to compete with Wal-Mart was not to copy them but to differentiate – in their case largely through store and product design.

When Austin-based Dell Computer first started up, I was sure they would fail. What industry could be tougher than computer hardware? Surely the industry giants (led by IBM) would put them out of business. As the years went by, I kept hearing people say, “Dell computers are really inexpensive.” Having bought my first personal computer from Radio Shack in 1980, I’ve seen plenty of ads for computers saying “Ours are the cheapest.” It struck me that a low-price strategy would be the easiest to copy. I became even more convinced that Dell would not survive.

But then I started reading new comments in the computer magazines, things like “Dell is fastest of those tested” and “Dell has the best service and support of those we examined.” And my friends stopped saying, “Dell is the cheapest” and started saying, “Dell is the best value.” And they have not stopped saying it.

My last five computers have been Dells. Arch-competitor (and former industry leader) Compaq just announced they are not going to focus on hardware in the future, moving instead toward software and services. It appears they think that fighting Microsoft and Oracle will be easier than competing with Dell.

What goes into the value formula differs with each industry, with each company, even with different customer types. There is a different set of details if you are selling jets to British Air compared to the formula for selling Dairy Queen to Middletown. But there is always a value formula, and there is always a mix of things that go into it.

One of the most common mistakes is to forget that what the customer receives is not just a single item, but a combination of factors, a soup. It is not the salt or the vegetables alone that makes great stew, it is the combination. Too often I have seen a retail store drop a product line because it was unprofitable. But the most profitable retail chains usually have at least some loss leaders. Does Time magazine really know the exact value of having an obituary section? Do people pick up the Chicago Tribune only for the sports scores?

In the same manner, it is a mistake to believe that each transaction must stand on its own. The person who comes into your bookstore today and stands and reads a book for twenty minutes, then puts it back on the shelf, may tomorrow bring in a friend who buys $500 worth of books. The man who has been kicking Ferrari tires for six months may complete that real estate deal next week and walk in with half a million dollars in cash. In reality, we often do not make much money on any given transaction. But over the lifetime of a good relationship with a customer, we can earn a lot of money. Ask McDonald’s if you can get rich $5 at a time.

Each day brings new headlines and new books which claim that business is being revolutionized by this or that innovation. But a careful look at the success of the greats, and the failure of the not-so-greats, lets us know that nothing that really matters changes in business. The technologies come and go, new advertising media come and go, but what matters today is what mattered to the leaders of enterprises 50 years ago and 500 years ago – knowing your customers, caring about their needs and desires, and working around the clock to anticipate and meet those needs and desires.

This remains true today whether you run Wal-Mart, Harvard, or the local luncheonette.

|