What better time to talk about retailing than Christmas week, the peak of the year?

This widely-read recent online post declares the coming death of the shopping mall.

I don’t believe malls will die anytime soon, and probably not in our lifetimes.

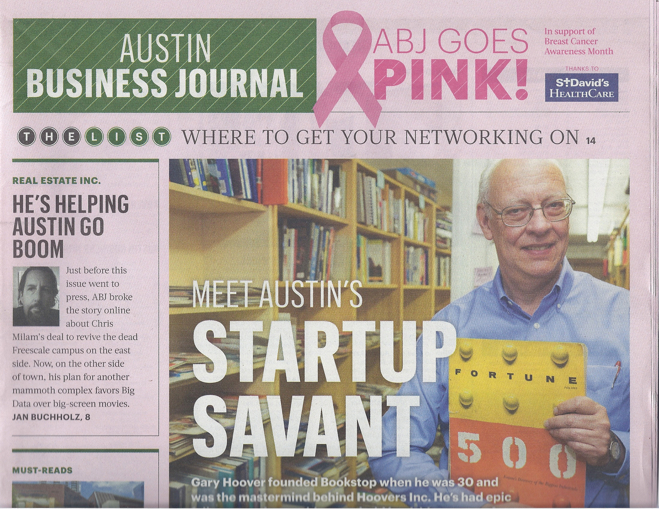

I have spent my life in retailing and retail real estate. 34 years ago I was in charge of marketing and strategic planning for one of the 20 largest mall developers. At that time, I made a presentation to top management claiming that regional enclosed malls had peaked and would continue to lose market share. I have seen, heard, and said a lot on this subject over the years.

What is a “Mall?”

The first task in understanding is to clarify the terminology. In the industry, there is — or was — no such thing as a “Strip mall.” “Mall” meant a large regional shopping center of substantial square footage anchored by department stores. While some of the early and late ones were unenclosed, the primary mode of operation was the enclosed mall. Strip shopping centers were almost never enclosed, and were also called community or neighborhood shopping centers. These were and are very different properties with different dynamics and fates. Since then, many innovations have come along, with various names and buzzwords.

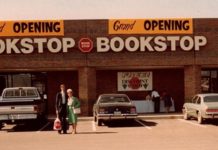

Strip centers historically were anchored by food and drug stores, serving a smaller radius of customers than big enclosed malls. This changed with the rise of the superstores or category killers — single category stores with dominant selections and aggressive pricing like Barnes & Noble, Staples, Home Depot, Best Buy, Toys R Us, and Bed Bath and Beyond. Their huge market share gains were the main driver of creeping mall market share loss that I noted 34 years ago. These operators historically preferred to be outside the big malls because they have easier parking, can have longer hours, lower rent, and just as importantly lower common area and other charges, including real estate taxes. I led companies which built 26 such stores.

This big rise resulted in a new type of strip center, often with no grocery store, filled with superstores and rounded out with restaurants and service businesses like insurance agencies, hair cutting, and medical and educational services. Sometimes these were called “power centers” or “lifestyle centers,” especially if they served more affluent customers.

Any look at new and vibrant strip centers today will show you how they are increasingly less oriented toward selling stuff — merchandise — and more oriented toward services. Some new centers are 80-90% services, from minor emergency medical centers to banks and restaurants to Sylvan Learning Centers. The rise of services reflects the global and national rise of the service economy, which has been proceeding apace for decades.

As always, retail real estate developers will react to tenants’ demand for space, which tenants are in turn reacting to changes in consumer demand.

Other innovations over these years include outlet malls and high-end open-air centers as pioneered by Easton Town Center in Columbus, Ohio, and now known all over the nation (e.g., Atlantic Station in Atlanta, The Grove in LA, and The Domain in Austin).

Most all of the shopping center types listed above are in pretty good shape today, though it depends on the market (demographics and trends) and merchandise mix, as it does for the big regional malls discussed below. Each property is unique.

“Real” Malls

Now to the big regional (usually enclosed) malls that I think this post relates to the most. They are grouped by the industry as A malls, B malls, etc.

Most of the A malls in the US are very healthy and making money for their owners and most of their tenants. Check out South Coast Plaza in Orange County, and some of the comments on the linked post about how busy the malls are. “A” malls were historically made “A” by having the strongest department stores, in the old days Sears plus the local version of Macy’s. A Nordstrom changes everything, and an Apple store is another boost.

Weaker B and C malls have typically been weaker from the get-go. In Chicago, the “winner” malls like Old Orchard had Sears and Marshall Field while the “loser” malls had Montgomery Ward and Carson Pirie Scott, the weaker sisters. With the endless competition of retailing, many of them will fail.

Selected malls have witnessed dramatic shifts in their demographics. Sometimes accompanied by higher crime rates. There is a website devoted to dead malls. Here in Austin, the largest mall when I moved here, dominating the city, totally closed up due to those changes coupled with the construction of newer competing malls as the market grew. That mall, Highland Mall, has been converted to a massive learning center and the key location of giant Austin Community College, along with a major facility for technology leader Rackspace. In nearby San Antonio, Rackspace converted a dead mall to their headquarters.

Converting malls to other uses is much trickier than one might think. These places were built as temples to merchandising, with parking and delivery arrangements, leases and financing customized to retailing. They would be very expensive to convert to offices or apartments. They are usually precisely located at an ideal point where major arteries or freeways come together, ideal for retail. So the odds are high that most will remain retail, restaurant, and entertainment centers. The older ones have been “remixed” to respond to changing consumer preferences, and will continue to be remixed.

My colleagues and I are developing a new “edutainment” concept called The Spark. Chances are high that some of our future locations will be in the best malls.

An important differentiation is between growth in absolute numbers and growth in market share. Macy’s, the result of multiple mergers, today is larger than when i worked for two of its predecessor companies. But my analysis of census bureau data indicates that they and their competing traditional department stores have lost dramatic market share in their key category and leading source of profitability, women’s apparel. Interestingly, the gains went not to general merchandise discounters like Walmart or warehouse clubs like Costco, but to Old Navy, the Gap, and more importantly Ross, Marshall’s, and TJ Maxx (whose parent company TJX is America’s most profitable big retailer on a return on invested capital basis).

Likewise, strong malls will continue to shift their mix and continue to show increased sales, but their share of the total retail market will likely decline.

These shifts result from the mix shift of US consumption. Food spending as a share of income has declined dramatically over the last 100 years and continues to do so. Apparel is one of the slowest growing categories, but like food it is so big there is always room for a hot small company (I served 4 years on the Whole Foods Market Board of Directors — a great company but still a minor player in the big picture of US grocery sales).

As the baby boom matured and had kids, we saw big rises in spending on books, pets, sporting goods, toys, auto parts, electronics and other “hard goods” categories. I believe that the abdication of these departments by the Macy’s of the world (in their pursuit of the higher gross margins realized in apparel and other soft goods) is one of the major reasons for their relative decline, and that of the malls.

But none of this means the malls will die. The best managed and mixed ones will continue to increase revenues, and some will increase their share of the ever-growing consumer spending pie.

Ecommerce

Online retailing is the most oft-mentioned factor in “death of retail” stories. But the latest federal data (3rd Quarter 2015) shows ecommerce is at 7.4% of US retail sales, versus 6.5% a year ago and 4.5% five years ago. Those numbers will continue to grow — I think it could hit 20% by 2030. So it is very small but growing rapidly. Again, it varies dramatically by the type of merchandise. If you take out the two giant categories of groceries and automobiles, these percentages are significantly higher. In some categories, like books and records (CDs), the industry has been turned on its head by emerging digital media and systems like iTunes.

But people do not really want to just sit at home and have all their meals and movies delivered. I think Aristotle said, “Man is a social animal.” That has not changed. But the mix of things we want has changed – look at people going to MakerFaire or hot concepts like Top Golf. Restaurants continue to gain share over grocery stores, and that industry will remain vibrant and a powerful reason to leave the house. And we have things like work, school, and church that make us leave the house anyway.

There are a great many factors at work, moving in multiple directions. Out of home shopping and entertainment will remain strong for many decades, probably forever, but the mix of services and products offered will continue to evolve. Some will go the way of record stores, but we cannot even imagine the new types of stores and services that will arise.

From the viewpoint of investing in real estate trusts, I think you really have to look at the quality of the properties and their management. While admitting that I know them — I originally hail from Indiana — I have observed the Simons of Simon Property Group (SPG) for 35 years. Those people fully understand all these dynamics. But ultimately they know they are sitting on gold in most of their properties, and I believe they will continue to exercise foresight in how to mix the centers. I have long sadly predicted the demise of Sears — and SPG has recently put together a joint ownership deal with Seritage to take over many of the best locations. Getting those giant spaces “back” will pose challenges to Simon, but long term it will likely greatly benefit them as they put in stronger uses and draws.

In my experience with thousands of companies and hundreds of industries, I have found few leaders who look out as far into the future as mall developers. In some heavily regulated locations, it can take over 10 years from the time you first envision a mall until it opens, and it only pays off big if it lasts for decades. Commercial real estate developers must look far over the horizon, studying the “big picture” of geography, demography, and consumer trends.

I can be reached at garyhoov@msn.com or see my blog at https://www.hooversworld.com and search on “retailing” for more thoughts on this subject which I love so much.

I hope this helps everyone in their thinking and analysis.

Happy Holidays!

Gary