I was working on a newsletter about Melville Shoe, a retailer I covered as a securities analyst at Citibank in the mid-70s. It was a great company with some unique approaches to opportunity discovery, with lessons to teach others, but forgotten today. The core was the Thom McAn shoe store chain (one of the big two, alongside Woolworth-owned Kinney Shoes), and the growth engine was Meldisco, a majority-owned joint venture with Kmart which operated the Kmart shoe departments.

I remembered that in business guru & then-Stanford-B-school-prof Jim Collins’ landmark best-selling first book, 1994’s Built to Last (about companies built to stand the test of time through visionary leadership), Melville was the “weak company” paired with “visionary” Nordstrom, which also began as a shoe store.

Collins tried to select pairs of comparable companies and look at them side by side, one “visionary” and one not. While I loved most of his principles & conclusions, I never really liked the pairing approach. There are relatively few highly comparable pairs in business history (City Stores & Mercantile Stores and Sears & Wards would work). And Collins, like most general business writers, did not have the depth of understanding of each industry required.

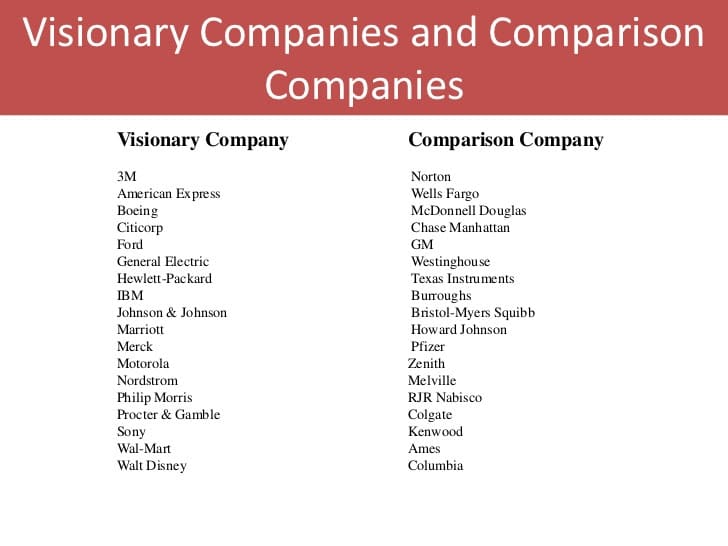

Here were his pairings:

As to Melville: in the late 60s, they had acquired a small Rhode Island based drug store chain called Consumer Value Stores, now CVS. And I thought likely outperformed Nordstrom, which is indeed an excellent company (I convinced a sell-side analyst to write the first Wall Street report published on Nordstrom).

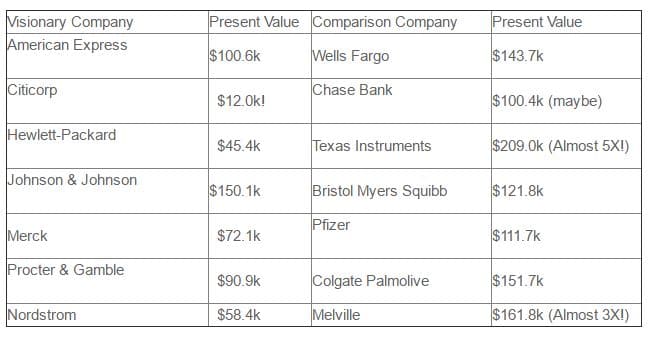

In looking up stock performance of the two companies since the 10/26/94 publication date of Collins’ book, through yesterday, i could not help looking up the other paired companies. 22 years is a long time, but Collins’ book was all about taking the long view.

What I found is amazing.

Here shown as “if you invested $10k in the stock the day the book came out, what would it be worth today?”

The above numbers cover 7 of his 18 comparisons. Collins was “wrong” on 6 of the 7. Only Johnson & Johnson beat Bristol Myers Squibb, and then not by a huge margin. Chase Bank is hard to determine because it is rooted in 3 big banks: Chemical, Chase, and Morgan Guaranty.

In many of the other cases, the comparison companies were acquired, some for cash, some for stock, so it would take more work to figure the answers. Often laggard companies turn out to be good investments when another company overpays for them. Ford clearly clobbered GM, because Ford never went bankrupt. Some like Howard Johnson and Zenith were really unfair choices, already on their last legs when Collins wrote. Norton, Kenwood, & Columbia were insignificant companies compared with their paired “visionaries.”

Certainly, at the very best, Collins’ picks would be 50/50, the same as darts, but probably worse.

What does all this mean?

Was Collins just stupid or “full of it?”

He has almost certainly made millions as a speaker and consultant.

I met him, a few years after his even more popular 2nd book, Good to Great. I genuinely complimented him on it, but also asked about his failed picks in that book, including the disaster that was Fannie Mae. But he still defended another pick, Circuit City, though I assured him it was a goner. He just did not study retailing closely enough. For more on his batting average, read this.

Certainly one lesson is not to believe “experts,” no matter their credentials.

But I think the bigger lesson is how hard it is to predict changes in companies and managements. Even Peter Drucker missed on some companies, like Sears that he thought was phenomenal — in the 1980s, ten years after top Wall Street analysts saw big chinks in their armor (and management). In my 2001 book, I said the Daimler-Chrysler deal seemed like a good fit….who would expect the great German automaker to screw it up, and the very weak Italian company FIAT to later save it?

Jim Collins worked hard to figure out what separates the winners from the losers, and most of his conclusions are still valid. But keeping a great company on track is a very difficult thing. That is one reason I have especial respect for those companies that seem to do it year-in, year-out, like UPS, John Deere, Caterpillar, Paccar, Costco, Johnson & Johnson, Colgate Palmolive, and many others.

Maybe all of us who write about business should be glad no one consistently and rigorously tracks the predictions of gurus. The many stock market and individual stock soothsayers may not have their feet held to the fire, either.

On the other hand, back-checking economic and business predictions might be an opportunity for a book or webservice, not unlike Politifact and Snopes.com.

In any case, beware of gurus, make up your own mind, and don’t give up hope if you work for or run a “weak sister” company! Focus on building a great, lasting business, not on what others say about your company.