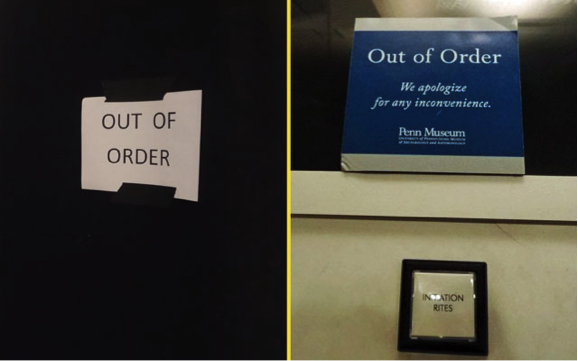

Do these pictures taken in museums look familiar? While museums and historic sites have improved over the years, in many ways they are not up to speed with the rest of society. This newsletter contains my thoughts on opportunities for museums to better serve society.

I am a museum lover and in recent years have become a museum critic, as in “movie critic.” I developed a concept for a “new era” museum in 2006 and 2007 but hit the recession of 2008 and could not raise the required funds. I am now embarking on a new museum project and beginning to raise funds. In my research, I have visited an estimated 600 museums around the world.

In the museum industry, I have noted two schools of thought, one of which defends the old guard and sees little need for my type of ideas, while there are others who eagerly seek such innovations and improvements. My emphasis here is on the museum as a critically important part of our educational system, rather than the archiving and preservation roles that many museums also serve.

These thoughts reflect a world in which education is more important than ever, but evolving rapidly with great innovations like Ted conferences, Khan Academy, Lynda.com, Udemy, and Coursera. We also live in a world where the public is daily offered immersive, engaging experiences, whether at stores like Nordstrom and Whole Foods Market, at Build-a-Bear and Apple stores, in Puzzle and Panic rooms, at SXSW and Maker Faires, and in experiences like iFly and TopGolf. The expectations of the public are higher than ever. The museum business has boomed. Between 1997 and 2012, the Census Bureau reports that American retailing grew 71.6% and “amusement, gambling, and recreation” grew 69.0%, while “museums, historic sites, zoos, aquariums” grew 102.8% and for-profit museums grew 152.5% (to $1.2 billion in revenues). Nevertheless, the industry has not kept up with these trends in society. Here are some ideas on how to catch up.

1. Visitor focus.

Today many museums place a greater emphasis on donors than on visitors or guests. In my hundreds of museum visits, only twice did I find the head of the museum on the floor talking to “customers.” One was the director of the great Chrysler Art Museum in Norfolk, who I now discover is widely regarded in the industry as a visionary for his approach to customers.

At the other extreme, I have been rushed out of museums before closing time as they set up for private parties, despite paying over $20 for admission. Many museum executives do not work on Saturdays, whereas their industry is even more dependent on weekend traffic than are most retailers, who are at work on Saturdays. A big share of the booths at the museum trade shows are about fundraising and spotting donors rather than supporting the ticket buyers. Most of the following ideas are about how to better serve those public visitors.

2. Humanize.

Too much of what I see in museums seems aloof, distant, and irrelevant to our lives. Science museums rarely tell the story of the trials and tribulations of the great inventors and researchers. When I visit an art museum, I would like to know what the artist was like, where she lived, how his life progressed, whether she went insane from the chemicals in the paints, or why he cut off his ear. But usually all I learn are the name of the work, the date it was done, and who gave it to the museum.

Many museums make less eye contact than Wal-Mart, except for sullen security guards. Opportunities for visitor input or ways for visitors to in some way alter or create the museum are few and far between. I believe that the most important ingredient in immersive experiences is storytelling. As an amazing, positive example, visit the Holocaust Museum in Washington – it is essentially a complete chronological story, a truly three-dimensional “movie” that you walk through sequentially instead of passively sitting in a seat and watching. Like a great film, it has an intense emotional impact. (For more on this and other key concepts, check out this book).

3. Merchandising.

That word incorporates a lot of ideas, but in this case I mean “keeping the store fresh.” Retail stores and restaurants normally open at a level of attendance and revenue and then rise over time; many museums open strong then go into decline. Most people only visit the key museums in their community every 2-3 years (except for Children’s museums which have a different rhythm). Sometimes it takes an expensive blockbuster exhibit to get people back. This is because they do not change or re-arrange their stories (little or nothing is on wheels) and they do not continually excite and engage the visitor.

Every merchant knows you must continually freshen the store, even if it means just moving things around, or pulling something old out of the back and making a display about it at the front. Great merchants take their clues from the seasonal calendar, from holidays, or from the news. Historian Neil Harris points out that from about 1880 through 1940, Americans discovered new ideas in three places: museums, department stores, and world’s fairs. With the sharp decline of the latter two, museums are now the best places to explore the new and the future.

4. Convenience.

My years in the department store and bookstore industries led me to conclude that convenience is perhaps the most underestimated part of success. It is at least as important as pricing and sometimes even content. It is a key part of the success of Amazon, Walgreen’s, CVS, Sheetz, and Wawa. There are several components to convenience, including location (be near your competitors; cluster museums into districts), parking, hours (many museums close at 5PM, just when people have free time), and sight-lines (in one popular music museum, every exhibit label was at ankle level, impossible to see when crowded).

Consider museum websites: if you type into a Google search box the name of most any museum, you find the most common searches come up in a dropdown list from Google. These often read something like “museum of art parking” or “museum of art hours.” The most important information for any bricks-and-mortar retail or service business is, “Where are you, what times are you open, and how much do you charge?” Yet most museums do not put this information on the home page, and sometimes it is buried two or three levels deep, below “planning your visit.” Even those which put their hours on the home page place them well “below the fold” in small type, failing to reflect their critical importance. People love easy, not hard! Compare the home page of the for-profit International Spy Museum!

5. Integration.

On my first visit to the beautiful Georgia Aquarium in Atlanta, I was blown away by a stunning exhibit on jellyfish, some of the most beautiful and dangerous beings on earth. They swam all around the glass tube I walked through. At the end of my visit, I went to the large gift shop and asked for something related to the jellyfish. They proudly showed me key chains, stuffed animals, and t-shirts. Over and over again, at museums, I have to ask, “Where is the nearest bookstore?”

Museums draw among the most educated customers of any industry, yet many do not respect those customers. I was especially surprised that this was the case at the aquarium, given primary funding came from one of the brilliant founders of retailer Home Depot. Even museums with great bookshops often do not integrate their merchandise with the exhibits. I get the sense that the people running the gift shop and selecting the merchandise are not in communication with those running the exhibit areas.

In the great art museums, which often do have great bookshops, I still walk through the place compiling a list of books I would like to buy or artists I want to learn more about. Why should I have to wait until I am done with my visit? In this era of easy payments and ordering, there should be a way to select items as I walk through. Those at the top need to conceive of their facility as one integrated experience for the customer, not a museum next to a gift shop next to a café next to a parking lot, all of which are only loosely related.

6. Maintain.

This goes back to the picture at the top. The number of “out of order” interactive exhibits is far too high. In my plans, my rule is “every experience is working or is taken off the floor immediately.” Put casters on those exhibits so you can wheel them away! When I visited the Independence Hall visitor center in Philadelphia, all the rest rooms were out of order or had no toilet paper – at any well-run retail store, that would never be tolerated.

7. Imagination is more important than money.

I toured one of the nation’s top science museums. The exhibit staff member who hosted me expressed frustration. They had just spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on some huge new exhibits but still the lines were longer at the two cheap outside exhibits. One was a retired centrifugal amusement park ride, where you stand up and spin around in a circle, and the other was a pickup truck on a platform at the other end of a giant lever – even kids could pull the rope that dangled from one end, lifting the pickup truck on the other end into the air.

Some of the best truly interactive exhibits I have seen did not have a computer in sight – they were entirely powered by Post-It notes and Bic pens! In St. Louis, the late artist Bob Cassilly opened the City Museum in 1997. This “playground for people of all ages” in a former shoe warehouse is one of the most exciting and engaging of the 600 museums I visited, drawing over 700,000 visitors a year. Yet his capital investment was far below that typical of museums. It was built on imagination.

Architects and exhibit designers often do not have a high priority on reducing the budget or scope of the job. In my experience as an entrepreneur, I generally believe I should be able to deliver twice the quality at half the price of established organizations by rethinking things from scratch.

8. Understand and analyze the numbers; make use of the data.

Many museum leaders are not comfortable with budgets, spreadsheets, and financial analysis. But understanding the numbers and how they relate to each other are key parts of any successful venture, for profit or not.

- What is your trade area?

- Do you capture zip codes of every visitor?

- Have you devoured this book?

- How much is your earned income per visitor and per square foot?

- How much is your capital investment per annual visitor?

- How many visitors per square foot do you draw?

- What is your average price per hour for your visitors?

- Might it make more sense to lease rather than own your artifacts, exhibits, and buildings?

- How good is your Executive Director’s dashboard or balanced scorecard?

- How do you stack up in these regards with other museums and with amusement and entertainment competitors like movie theaters and Family Entertainment Centers (FECs)?

I have seen some progress since I first studied the industry ten years ago, but in today’s era of big data, the opportunities to learn from the numbers and other more qualitative inputs are greater than ever.

9. New dimensions.

If you are building a new museum or expanding or rebranding, think in new dimensions. The International Spy Museum in Washington has been a big hit since it opened in 2002. It attracts over 700,000 visitors a year at a pricey $22 per adult despite being surrounded by free museums like the Smithsonian. It is true “edutainment” if you are willing to use that awkward term. When I began to think of creating a new museum, I started listing all the different subjects where few if any museums exist: the museum of the home, of the office, of weather, of the brain, of religion, of advertising and graphic arts, of education, of travel, and on and on.

Since my studies, the National Museum of Crime and Punishment has also opened in Washington to rave reviews and solid attendance. Most subjects that are of interest to people have not been touched with this kind of experiential education focus. Some of my friends said, “Well the Spy Museum is different, everybody loves spy stories.” But that is nonsense: any subject in the hands of the right storyteller can be compelling and of interest to a wide swath of the public. Look at the PBS and other TV specials which many would have thought “that does not sound interesting.” Not until you put it into the hands and cameras of Ken or Ric Burns!

10. Build chains.

This suggestion is more complex and advanced than the others. As I studied the museum industry, I realized it was really weak in human development in the sense that the number two person in a museum must wait for her boss to move on, or she must move on herself in order to personally grow.

One of the many great strengths of retail and service chains are tremendous opportunities for personal growth. These organizations have training and development systems that insure growth opportunities for the most talented people.

Chains also reduce costs dramatically – whether it be by having one buyer select all the books for 10 or 100 stores, or by the fact that if you make two copies of an exhibit at the same time, the cost of the second one should be a fraction of the cost of the first one. The Guggenheim and the Smithsonian have both dabbled with co-branding in multiple facilities with mixed success. Nevertheless, there should be ways to share, work together, partner, and affiliate to get some of these advantages, even without doing the full chain concept like Ripley’s Believe It or Not or Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museums.

Conclusions

As I continue to visit museums and other tourist attractions, I see many signs of progress. There are exceptions to every complaint I have listed above. Children’s and science museums in particular are more impressive than many history and art museums. For-profit museums are especially booming: they are healthy taxpayers and they have an intensified incentive to focus on the satisfaction of visitors, not donors.

I am in the early stages of raising the capital and developing the concept for a new era “Museum of Innovation” which I would like to build in here Austin. Our great city is one of the most technologically advanced, best educated, and fastest growing American cities, but we have a shortage of science and technology museums and other “edutainment.”

In cities around the world, strong, financially secure, popular museums which educate the public in fun and engaging ways will continue to play a key role in how we learn about and comprehend the world around us – past, present, and future.

Please let me hear your ideas, thoughts, and comments here on LinkedIn.

Gary Hoover

If you would like to subscribe to the twice-monthly newsletter click here.

To see more articles like this, visit my website Hooversworld.